Despite drastic changes to the iconic accent, most Texans will continue to use their twang in the right situation

Since this story was featured in Life & Letters last spring, English Professor Lars Hinrichs’ research on the evolution of the iconic Texas twang has been featured in several national media outlets, including TIME, NPR and ABC News. As part of his Texas English Project, Kate Shaw Points, a linguistics graduate student, has discovered some surprising findings about Texas twang in East Austin. Read her Q&A to learn more about her work.

Venture into a honky-tonk or a rural Texas town, and you’re likely to find more slow-talking cowpokes than you can shake a stick at. Yet researchers at The University of Texas at Austin have found “Texanisms” such as “might could” and “down yonder” are dissipating, especially among young city slickers.

Is the Texas twang fixin’ to die out? Not necessarily, says Lars Hinrichs, assistant professor of English language and linguistics and director of the Texas English Project. Despite the drastic changes in the Lone Star State’s iconic accent, Texans will continue to use their twang, but only in certain contexts.

“Although the dialect is far less prominent in Texas, people still speak it,” Hinrichs says. “But it depends on whom they’re talking to, what they’re talking about and whether it triggers their Texas pride.”

As part of the Texas English Project, which began in 2008, Hinrichs and his team of student researchers are collecting dozens of interviews with native Texans and documenting the various factors that influence how they speak. According to their findings, the local dialect is becoming more of a choice rather than a function of place.

Language as a Social Commodity

So is this wishy-washy shift in dialect a sign of the times? According to Hinrichs, urbanization, technology and the influx of newcomers are all contributing to the erosion of the Texas twang.

“Thanks to high mobility and rapidly increasing access to mass media, people are looped into the majority culture and seek identities that integrate both the local and national,” Hinrichs says.

And this isn’t just happening in Texas. The distinctive sounds and vocal patterns of America’s regional accents — like the way Bostonians drop the “r” in some words — are rapidly transcending into a more homogenized Midwestern American dialect, Hinrichs says.

“People grow up with good access to resources that teach them to speak dialect-free standard English,” Hinrichs says. “But they frequently choose to use dialect speech to their advantage when they want to appear more genial.”

“People grow up with good access to resources that teach them to speak dialect-free standard English,” Hinrichs says. “But they frequently choose to use dialect speech to their advantage when they want to appear more genial.”

Texas women, for example, tend to stifle their twang to avoid sounding uneducated. But they can use their accent to their advantage in business interactions when they want to exude an air of Southern hospitality, Hinrichs says.

Drawing from research by Barbara Johnstone, a sociolinguist at Carnegie Mellon University, Hinrichs found that although women tend to use the twang to their advantage, they are the first to replace it with the new regional dialect.

“Young Anglo women are leaders of accent change — and they are members of the social/ethnic majority,” Hinrichs says. “They have an ear for linguistic prestige and are the first to adopt the modernized features of speech.”

The identifying mark of Texas and Southern accents is the flattened monophthong, a vowel with only one part. Every accent has a monophthong, but Southerners and Texans alike put their own unique spin on it. For example, Texans have a way of using the “ah” sound in words like “pah” (pie) and “naht” (night).

In contrast, Midwesterners and Northerners enunciate these words with a strong “ie” sound. So when Texans say “pah,” their Yankee counterparts say “pye.” This sharp “ie” sound is what linguists call a diphthong, a vowel with two parts. Examples of Tex-ified diphthongs include “tray-up” (trap) and “fah-ees” (face) and “kay-ut” (cat).

The diphthong is another emblem of Lone Star speech. These old-fashioned down-home drawls have long been embraced by generations of Texans. But Hinrichs’ research shows the telltale marks of the Texas twang are rapidly falling to the wayside as young women consciously stifle their accents in fear of sounding like a redneck.

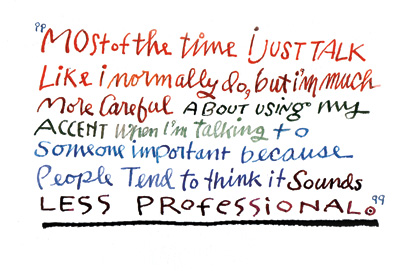

Emily Edwards, a 23-year-old Liberty, Texas native, says she tries to muffle her distinct East Texas drawl when giving presentations at school or speaking to people outside her social circle.

“I didn’t realize how country I sound until I came to Austin and everyone remarked on my accent,” says Edwards, who is majoring in elementary education at Lamar University in Beaumont. “Most of the time I just talk like I normally do, but I’m much more careful about using my accent when I’m talking to someone important because people tend to think it sounds less professional.”

“I didn’t realize how country I sound until I came to Austin and everyone remarked on my accent,” says Edwards, who is majoring in elementary education at Lamar University in Beaumont. “Most of the time I just talk like I normally do, but I’m much more careful about using my accent when I’m talking to someone important because people tend to think it sounds less professional.”

But when she’s working at her small-town clothing boutique, she admittedly turns up the Southern charm to make herself seem more warm and inviting.

Hinrichs found men are also invoking their inner Texan when they want to present a friendly, hospitable demeanor. He stumbled upon this finding while observing young, urban Austinites interacting with customers at the Bouldin Creek Coffeehouse. To study how native Texans speak in a casual setting, Hinrichs and his team of student researchers videotaped their entire four-hour shifts. After transcribing and coding hours of audio recordings, they found even the young city-dwellers systematically revert to old Texas phrases at opportune times.

While ringing up his customers, Luke Malone, a 25-year-old native Texan, consistently used the old-timey Southern phrase, “Thank you kindly.”

“We found that the accent really comes out with the customers,” Hinrichs says. “The Southerner has the cultural advantage of being hospitable and friendly, so in the videos we saw them saying ‘thank you kindly’ a lot. It’s not actually a Texan phrase, but it’s used as a way to evoke an old cotton Texas personality.”

After observing the young baristas at work, the researchers bring them into the Linguistics Department’s phonetics lab to analyze their speech. The participants perform speech elicitation tasks, in which they read the story of “Arthur the Armadillo,” once in their natural speech, and again in their strongest Texas accent.

“To get a baseline of their maximum dialect speech, we asked them to sound really Texan,” Hinrichs says. “And we found all the textbook features of the Texas twang, like pronouncing words like ‘five’ as ‘faav’ and ‘pie’ as ‘pah.’”

Hinrichs says this finding confirms the Texas twang continues to exist as a resource, but people are using it more as a social commodity.

Switched in Translation

Although terms like “pole-cat” (skunk) and “miskeeta hawk” (dragonfly) have all but faded away, it isn’t unusual to hear “y’all” tossed around in conversations — even in big cities, Hinrichs says. This is especially prevalent among Texas-born Latinos.

“My graduate students, Patrick Shultz and Arturo Nevaro found Latino students at UT are sounding more Texan than their Anglo counterparts,” Hinrichs says. “It’s not a way of trying to be white; it’s a way of being Tejano.”

As part of the Texas English Project, linguistics graduate student Kate Shaw Points records and analyzes interviews with Texas-born Hispanic East Austin residents. Among her surprising findings she discovered Latinos are proudly embracing the dialect of their home state.

“Some past research has suggested that minority ethnic groups tend not to follow the language norms of the majority group,” Points says. “But I found they are using the Anglo pronunciations of the long ‘oo’ vowels, which was very unexpected.”

That “oo” sound is produced by what linguists call “fronted manner,” meaning they produce a single vowel with the tongue and lips in a fixed position toward the front of the mouth. When discussing topics like Tex-Mex cuisine, family and regional pride, the speakers often enunciate words like “fewd” (food) or “shew” (shoe).

But when the conversation turns toward local politics and gentrification, Points says her participants revert to Hispanic English, in which the sound is produced with the tongue toward the back of the mouth. One speaker, for example, switched to this dialect while venting about developers pushing her out of her beloved East Austin neighborhood.

So what’s causing this unconscious switch in accents? Points suggests it is a way of expressing a certain identity. When they are happily waving their Texas-pride flags, they tend to infuse some twang into their speech. But when they are staking claim to their East Austin neighborhoods, they employ the Hispanic accent to distance themselves from encroaching developers and affluent interlopers.

“Considering its settlement history and how much the area has changed over time, I couldn’t have picked a better place to study language change than East Austin,” Points says. “There’s two very different competing accents, and it all depends on the subject matter.”

These insights can help dispel harmful stereotypes about different ethnic groups — and hopefully increase a sense of tolerance for other cultures, Points says.

“Appreciating that different groups of people have varied linguistic patterns, and that none of these patterns are a priori ‘better’ than others, could lead to increased understanding of other cultures,” Points says. “The more you know about how an ethnic group outside your own uses language, you are better prepared to accept their culture.”

Times they are a-Chaingin’

Given its unique mix of regional dialects formed by German, Czech and Latino immigrants, Central Texas is the ideal place to examine changing language patterns, Hinrichs says. Yet it is surprisingly the least-researched area in the nation.

“Texas is unique because the cultural and linguistic mixing that happens everywhere is happening here very strongly,” Hinrichs says. “There is the strong influence of Spanish from the South and throughout the state, the traditional Southwestern dialect region and the traditional Deep South, as well as more mainstream American English forms coming in from the North — all in competition right here in Central Texas. That is a pretty exciting mix of influences.”

The Texas dialect, known the world over, has several local flavors — from the soft, rounder East Texas drawl, to the higher-pitched, nasal Texas twang of the Panhandle. But in just three short decades, Hinrichs found the Texan way of speaking appears to be slipping away.

The Texas dialect, known the world over, has several local flavors — from the soft, rounder East Texas drawl, to the higher-pitched, nasal Texas twang of the Panhandle. But in just three short decades, Hinrichs found the Texan way of speaking appears to be slipping away.

He came across this startling discovery while combing through years of audio-recordings conducted by Gary N. Underwood, associate professor emeritus of English at The University of Texas at Austin. Hinrichs and his team also analyzed research from the late E. Bagby Atwood’s “The Regional Vocabulary of Texas,” a collection of words, phrases and vocabulary differences across Texas in the 1960s. Atwood was a linguistics professor at The University of Texas at Austin and a leader in the field of sociolinguistics.

“We transcribed and documented hours of Dr. Underwood’s interviews with Texas speakers and found the majority of his respondents had a strong Texas accent,” Hinrichs says. “But within the span of three decades, I’ve found only a small minority of Texans speak that way anymore.”

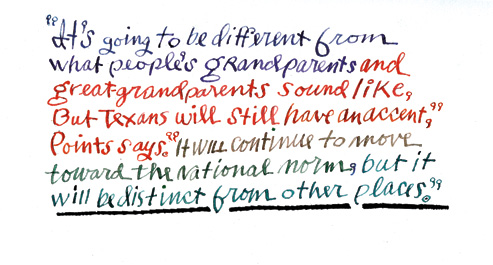

So what will become of the Lone Star State’s trademark accent in the next 30 years? Points maintains that although the twang will no longer be hotter than a two-dollar pistol, it will continue to be a part of Texas’ linguistic landscape.

“It’s going to be different from what people’s grandparents and great-grandparents sound like, but Texans will still have an accent,” Points says. “It will continue to move toward the national norm, but it will still be distinct from other places.”

As the world changes at an ever-increasing speed, so do languages, Points says. It is a natural process that occurs in the trappings of time.

“Languages change naturally over time,” Points says. “The way we speak English today is different from how Shakespeare spoke English. It’s not a bad thing that language changes — it’s a natural evolution.”