While the study of Jewish Latin America and Jewish Latinas/os might seem a small and specialized niche, the themes that emerge are often universal: cultural clashes, assimilation and blending in, loss, being part yet apart. Students and scholars of Latin American studies often ponder these very same questions.

When these two disciplines meet or overlap, as they do at The University of Texas at Austin’s Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies, there is an opportunity for deep intellectual exploration, and in many cases, self-reflection as well.

Established in 2007, the Schusterman Center (SCJS) offers a multidisciplinary undergraduate curriculum as well as public programming focused on diverse aspects of Jewish life and culture—including that of Latin America.

According to founding director Robert Abzug, who holds the Audre and Bernard Rapoport Regents Chair of Jewish Studies, the study of Judaism in the Americas is central to the Schusterman Center’s work. “About 47 percent of the world’s Jews live in the Western Hemisphere,” says Abzug. “And while the majority of that number live in the U.S., Latin American and Canadian Jewish communities are in touch with each other far more than indicated in the academic literature. We are hoping to set that right and thus make a large contribution to Jewish studies generally.”

Jewish Life in the Americas

As part of its Initiative on Jewish Life in the Americas, the center brings speakers and performers to campus whose expertise includes Latin America, the United States, and Canada. This initiative will now be expanded as the Edwin Gale Collaborative for the Study of Jewish Life in the Americas, to be developed by Professor Naomi Lindstrom, Gale Family Foundation Professor of Jewish Arts and Culture. Lindstrom teaches in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese in addition to serving as SCJS associate director. She explains how the Gale Collaborative will allow deeper exploration of the Jewish–Latin American and Latino connection:

“By allowing us to sponsor the visits of Latin American Jewish creative people and intellectuals, including Latino Jews in the United States, the Gale Collaborative will help us strengthen our ties to LLILAS and to departments, such as Spanish and Portuguese and Mexican American and Latina/o Studies. It will integrate us more fully into our university, which is widely regarded as the major hub of Latin American studies in the U.S.”

An interdisciplinary symposium on Jewish life in the Americas is in the works for November 2015.

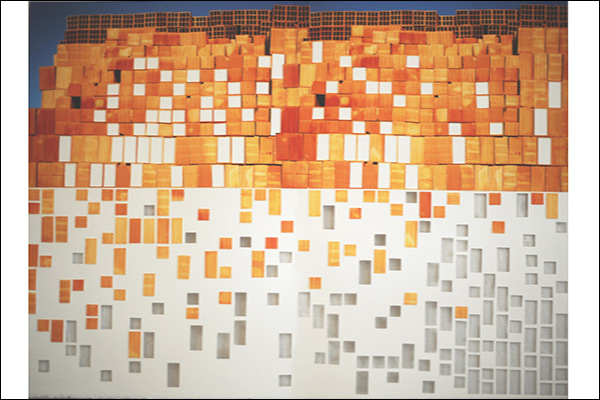

In June 2013, the Schusterman hosted the annual conference of the Latin American Jewish Studies Association (LAJSA). On the occasion of that conference, participant Stephen Sadow donated a one-of-a-kind collection of original art by Latin American Jewish artists, which is now on rotating display in the SCJS library and available to researchers. This collection is comprised of books containing original art and poetry, the product of collaborations between 28 Jewish writers and artists from eight Latin American countries. Sadow, a professor of Jewish studies and Spanish and Latin American literature at Northeastern University, cited the Schusterman Center as being the “perfect home” for these unique works due to the importance of Latin American studies at UT Austin.

Opportunities for Research and Collaboration

In September 2014, the center announced its second annual research travel award for a Latin America–based scholar. The award enables the scholar to conduct research on Latin American Jewish topics at The University of Texas at Austin for a period of seven to fourteen days. The first recipient of this stipend was Brazilian historian Bruno Feitler of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). At a talk in the center’s conference room last October, Feitler discussed his research on Jews and Judaism in Dutch Brazil (the Dutch controlled much of Northeast Brazil from 1624 to 1625, and 1630 to 1654; the synagogue in Recife, state of Pernambuco, is the oldest in the Americas).

Feitler’s work and interests overlap with those of Schusterman Center faculty member Miriam Bodian, a professor in the Department of History who specializes in the Spanish and Portuguese Inquisitions and post-Expulsion Sephardic Jewry. When the descendants of forcibly baptized Jews in Spain and Portugal, known as conversos, began fleeing the Inquisition in a northward direction in the early modern period, Amsterdam and Recife were among the few places where they could establish openly Jewish communities.

Both Feitler and Bodian dig deep into the historical records on two continents to explore the complex results and repercussions of the Inquisition, which reverberate today among Latin America’s Sephardic population as well as those Latin Americans and U.S. Latinas/os who have reason to believe that their ancestors might have been conversos or crypto-Jews. (The question of why this quest is problematic and why Jewish roots are often impossible to substantiate came up after Feitler’s talk, as did a debunking of the notion that certain common Spanish and Portuguese names are indicators of Jewish ancestry.)

Feitler’s travel stipend afforded him the opportunity to spend time at the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, where he was able to consult many publications that are not easily accessible in Brazil. “The Benson gathers an invaluable collection of works regarding Judaism in Latin America,” says Feitler. “My time spent there, thanks to the Schusterman Center, was useful as a way of updating my bibliography on the marrano question in Brazil, one of my subjects of study.” (Marrano is one of the terms used for Iberian Peninsula Jews forcibly converted to Christianity. Some of these individuals, crypto-Jews, gave the appearance of practicing Christianity while secretly continuing Jewish religious observance.)

The study of Jewish Latin America at UT is also pursued at the graduate level. In her doctoral work, Comparative Literature student Rae Wyse examines “how Latin American Jewish authors represent, negotiate, and define Jewishness in the Latin American context.” She is curious about “what motivates these authors to include Jewish themes in their works, who they address as their audience, and what implications these discussions have for how Jewishness is understood in Latin America.” Wyse says she has been able to easily and quickly access primary and secondary sources for her research via the Benson Latin American Collection, citing in particular the Benson’s holdings of works by Argentine poet Tamara Kamenszain, Chilean poet David Rosenmann-Taub, and Mexican writer Sabina Berman, among many others.

Courses and Special Events

The presence of several Latin Americanist faculty at the center makes the study of Judaism and Jews in Latin America an important component of Schusterman Center curriculum. Course offerings in the area of Jewish Latin America include Lindstrom’s: “Latin American Jewish Writers” and two classes taught by lecturer Amelia Weinreb: “Introduction to Jewish Latin America” and “Jewish Cuba.” And although Bodian’s courses on Jewish civilization from 1492 to the present and the Spanish Inquisition are not cross-listed with Latin American studies, it is not hard to imagine how they would enrich the student’s understanding of some of the powerful historical forces and events with impact in the Latin American arena.

Lindstrom’s current research concerns modern-day transformations of Latin American Jewish creative people working in poetry, the novel, film, and the graphic novel. These include Jacobo Fijman, a Bessarabian émigré to Buenos Aires who explored mysticism in his work and life; the Cuban poet José Kozer; Brazilians Samuel Rawet, Moacyr Scliar, and Clarice Lispector; and the Argentine-Spanish Kabbalistic novelist Mario Satz.

Weinreb discovered her interest in Latin American Jews via anthropology. She did her fieldwork in Cuba, examining the island’s changing national culture in the post-Soviet era, and it was there that she became interested in Cuba’s tiny Jewish population. Jewish Cuba is a writing-intensive course that examines questions such as: What is home? What is diaspora? What is revolution? Weinreb and her students work at how to write about such themes. In her course on Jewish Latin America, Weinreb emphasizes that “Jewish history in Latin America is world history.” From 1492, she says, Spain is seen as a “lost homeland” for Jews. Thus, she and her students explore history, memory, identity, and migration through a variety of readings that include memoir, folk storytelling, personal narrative, and ethnographies.

Fall 2015 promises the addition of a senior undergraduate course to be co-taught by Abzug and Lindstrom, Jewish Cultures of the Americas.

On Wednesday, Feb. 25, the Schusterman Center hosted a conversation about the recent mysterious and troubling death of Argentine prosecutor Alberto Nisman, who was found dead by gunshot mere hours before he was expected to deliver damaging testimony against Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and other top officials related to the July 1994 bombing of the AMIA Jewish community center in Buenos Aires. (Although officially ruled a suicide, many in Argentina are calling it murder.) Ariel Dulitzky, director of the Human Rights Clinic at the UT School of Law, and Sebastián Klor, a postdoctoral fellow at the Schusterman Center, was a speaker at the event. The Argentine Studies Program at LLILAS was one of the event’s co-sponsors.

On Thursday, March 26, the center will present a lecture by Libby Garland, author of the book After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921–1965. Among the themes Garland examines is the question of how a group of immigrants goes from being considered “illegal” and undesirable to being accepted and welcomed. Lindstrom says that the idea of inviting Garland to campus came from members of the Latino-Jewish Student Coalition, who are eager to hear Garland’s thoughts on the disparate treatment and attitudes toward immigrant groups throughout U.S. history. Next fall, the center will host Guatemalan Jewish novelist David Unger, winner of his country’s Miguel Ángel Asturias National Literature Prize.

The Schusterman Center’s commitment to the study of Judaism in the Americas opens the door for collaboration among Latin American studies, Latino studies, and Jewish studies, and for the continued pursuit of scholarship on diaspora, ethnic and national identity, borders and boundaries, language, and how these can shift and change depending on time, place, and context. The promise of such collaboration is the opportunity for deep intellectual exploration and, in many cases, self-reflection as well.

Feature Image: “On Construction” (2011), by Michal Kirschenbaum. Courtesy of Stephen Sadow.