In December of 2015, author and former Austin resident Ellen Sweets wrote a farewell letter to Austin that was published in TribTalk:

Ever since I decided to leave Austin, I’ve tried to write a farewell devoid of anger and frustration, and every time I’ve had to move on to writing something else. A Facebook post. An email. A grocery list.

I’d rather write about the vestiges of the Austin I once loved. The man in a Santa suit riding a horse along Montopolis. Or the person pushing the “walk” button at a heavily trafficked East Side intersection — there was nothing special about him except he was dressed in a chicken suit, head to clawed toe. I’d rather write about what I will miss, those glimpses of the funky Austin I used to know.

Instead, she wrote about a state, and a city, with a “pervading atmosphere of racial and religious bigotry.”

Maybe it’s Austin’s open secret, but most people who have lived here for any length of time notice that for a city that prides itself on its progressive nature, there’s a notable lack of diversity. Specifically, there’s been a marked decline in the African American population. This anomaly is so obvious yet so unexplored that KUT’s ATXplained focused on this issue for the first episode of the series in January 2016 asking, “why is Austin the only city in the country that’s experiencing a percentage decline of our African American population?”

To be more specific, Austin is the only major growing city in the United States that is losing African Americans. Eric Tang, associate professor in the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, was intrigued by this fact, as well as the ways in which Jim Crow segregation and neo-liberal gentrification converge here in what he describes as a “unique and intense” way. As he explains in an interview with Caroline Pinkston for an upcoming episode of the Humanities Media Project podcast Life of the Mind:

There is a way in which Austinites kind of know what’s happening, but no one really knows … Everyone kind of knows that there [was] Jim Crow in this city [and] that it was quite profound, if not always statutory, but they don’t really fully know. People kind of know that there is an area of the city cemetery that was designated for the burial of African Americans … Everyone kind of knows that, but no one really confronts these issues, and there’s no recognition.

Tang’s background in activism and his academic focus on underresearched communities and their relationship to larger issues of race, immigration and population, helped him formulate East Avenue, a close collaboration between scholars, community leaders and community members to document and analyze racial and economic segregation in Austin, Texas, and its effects on the city’s African American community. The goal of East Avenue is to provide research that will help shape initiatives to bring greater equality to the city.

A Brief History of Segregated Austin

The heart, or better yet spine, of the East Avenue project is the downtown section of Interstate 35, which was once known as East Avenue. In recent history, I-35 has been unofficially known as the dividing line between white Austinites, who until recently tended to live west of this section of highway, and nonwhite Austinites, who tended to live east of it. This designation is itself problematic because, as Dr. Joseph C. Parker Jr., pastor of Austin’s David Chapel, explains in a recent interview for an upcoming episode of the Humanities Media Project’s Homelands series, it means that the phrase “East Austin” is code language for black and brown people, a terminology that needs to change.

This wasn’t always the case, however. Prior to 1928, African Americans lived in various neighborhoods throughout the city, including Wheatville and Clarkesville. In that year, the City Plan Commission of Austin wrote up “A City Plan for Austin, Texas,” which institutionalized racial segregation. The plan explicitly stated that one of its leading goals was to compel African Americans to leave their homes and remove themselves to a “Negro District” containing all of the city’s black schools, black parks and black facilities, ostensibly in order to reduce racial friction and other issues caused by segregation.

By 1930, 80 percent of Austin’s African American community was on the east side, and throughout most of the 20th century this area remained home to the city’s largest concentration of African Americans. Efforts to maintain this segregation also continued.

In 1975, a battle waged over whether the full span of 19th Street from its easternmost end at Ed Bluestein Boulevard to its westernmost at North Lamar Boulevard would be named Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. A group named the West 19th Street Association fought the extension of the name change west of I-35, claiming that it would cost businesses too much to change their signs, letterhead and advertising. Additionally, they claimed, it would impinge on property rights.

Interestingly, 19th Street had historically been a connector of east and west, and this group wanted to literally end that by having Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard end abruptly at I-35. Until the late 1880s, 19th Street was known as Magnolia Street, and it supported businesses on both sides of East Avenue. Although it was not as active as East 11th or 12th streets, 19th continued to intersect the 6 square miles of the city’s “Negro District” as laid out in 1928, serving as a physical connection to West Austin.

“… African Americans who moved out of the city still feel an ineluctable bond with their historic communities — there’s this sense of historical, cultural and social rootedness that one can’t easily replace, no matter where one moves.”

Eric Tang

Representatives from the Austin Black Assembly, including Dr. Freddie B. Dixon Sr., former minister of Wesley United Methodist Church, eventually persevered, and the city named the whole of 19th Street in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. This victory was a symbolic beginning to the inclusion that needs to happen, according to Parker, but not an end.

In the 1990s, East Austin became a primary site for gentrification, and by 2010, the African American population was no longer a majority, as many longstanding residents had sold their homes to higher-income buyers before moving out to the suburbs.

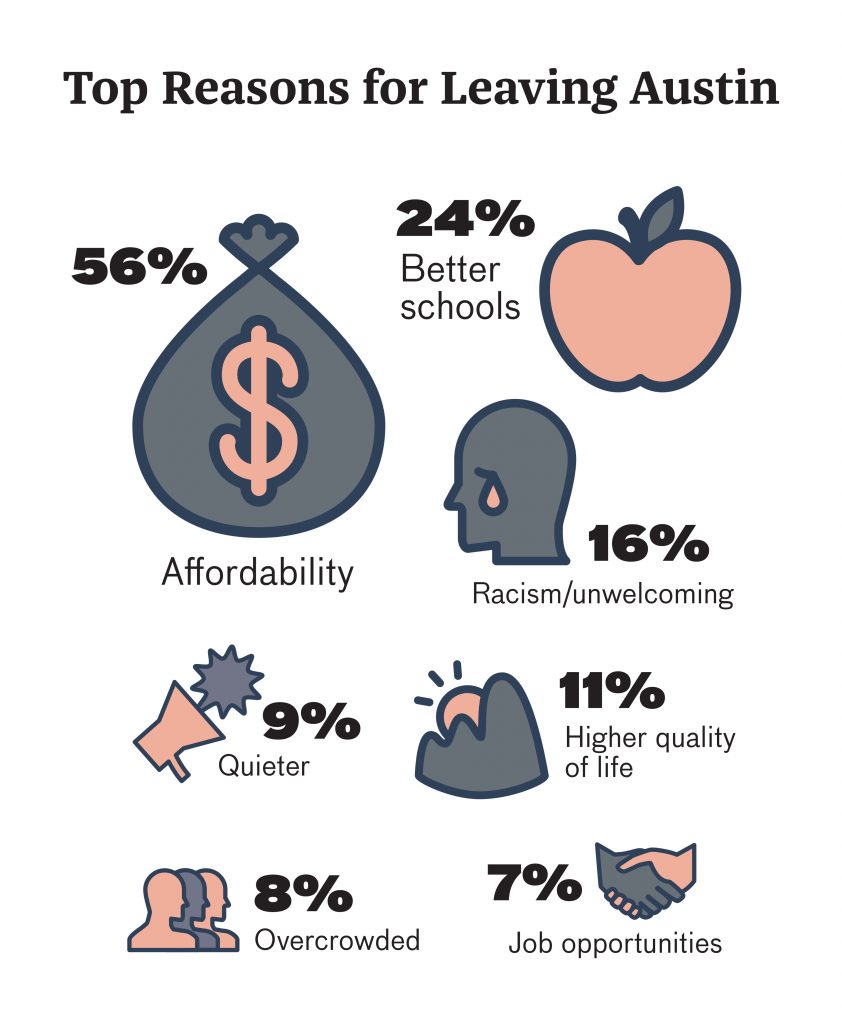

The precursor to the East Avenue project was a 2014 Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis issue brief authored by Tang and institute postdoctoral fellow Chunhui Ren that explored this phenomenon. “Outlier: The Case of Austin’s Declining African American Population” drew upon U.S. census data to reveal Austin’s rapid decline in African American residents between 2000 and 2010, despite its position as the nation’s third-fastest growing city. The brief postulated that the declining number of African Americans in Austin was the result of persistent structural inequalities. That is, African Americans did not choose to leave Austin so much as they were compelled to leave by historical, economic and governmental forces that continued to create inequalities in their lives. These forces included segregation followed by gentrification, policing, educational disparities and a lack of economic opportunity.

According to Tang, the East Avenue project was inspired by the passionate public discussions that attended the findings of this brief. Many people, “including journalists,” he said, “questioned whether or not African Americans were really being ‘pushed out’ of Austin,” wondering whether they left for better opportunities elsewhere. Tang’s response was simply to ask people why they left.

Take Me to Church

So, in Tang’s words, “they went to church”; many African Americans who left the city limits for surrounding suburbs still came back to East Austin for church on Sundays. Working with church leaders to identify congregants who had moved to the suburbs, he and his team surveyed individuals, asking them not only to describe why they moved, but also to evaluate their quality of life since moving. The responses showed that the majority moved because housing was unaffordable within the city; they felt that Austin schools were too racially segregated; and they were feeling the “gentrification squeeze” in soaring property taxes. Ironically, changes that might be seen as improvements, such as sidewalks and pocket parks, also served to drive people out, as these fueled more gentrification and thus higher property taxes and less money to spend on necessities such as health care.

Additionally, others pointed to racism they had experienced in the city. Sometimes this took the form of negligence. Parker says people are moving into these neighborhoods with skills and experience, but they are using these to benefit only themselves, not the community they have joined. In his Life of the Mind interview, Tang says that up to 30 percent of respondents in the open-ended section of the survey expressed frustration with how new arrivals to the neighborhood focused more on walking their dogs than on getting to know their neighbors. They treated the streets as a dog park, and this became a sort of unofficial symbol of gentrification.

The respondents’ stories held a few revelations for Tang and his team. They expected that affordability would be a popular reason for people to leave, but they were interested to see how many African American parents were dissatisfied with the Austin public schools and moved based on a desire to place their kids in better school districts.

Tang says that the biggest surprise for him was the number of people who said they would move back to Austin if they could. This included the people who moved north, who gave high marks to their current quality of life outside of Austin, including better food stores, better parks and better access to health care. As he states, “this suggests that African Americans who moved out of the city still feel an ineluctable bond with their historic communities — there’s this sense of historical, cultural and social rootedness that one can’t easily replace, no matter where one moves.”

Perhaps most importantly, these respondents missed their spiritual community. As Tang points out, they were hearing those stories in a church, on a Sunday, in a place to which they had returned.

Beyond East Avenue

Bisola Falola, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Geography and the Environment, and Chelsi West Ohueri, a research project manager in the Dell Medical School, helped Tang create and administer the surveys, collect and analyze data and complete the final report, “Those Who Left: On Austin’s Declining African-American Population.” Tellingly, they both heard about Tang’s work through community events. Falola saw how the work in East Austin fit with her research interests in its focus on issues related to place, race and access to opportunities. Ohueri also saw her research and her concerns in her new position as a cultural and medical anthropologist overlapping with Tang’s work in terms of housing, space and relocation issues.

Initially Falola expected that some factors, such as access to education, would probably have improved as a result of the respondents’ move to another area. Both she and Ohueri were curious about what Falola called “the starkness of geographic differences” between those who moved further east and ended up with less access to social resources, and those who moved north and ended up with more access. In short, residents who left central East Austin with fewer financial resources did not escape the legacy of resource discrepancies, including health care, that had shaped their previous community.

Ohueri and Falola found that most of the people they approached wanted to tell their stories and to keep up with the project. Falola specifically said that there was a need to have these stories about leaving Austin, not necessarily by choice, in the public consciousness.

“There was a recognition that this form of public sharing — that was research-based, tied to policy, and would appear in informal channels such as the media — could help raise meaningful awareness to the gentrification that has and continues to be taking place in East Austin,” says Falola, who notes that public scholarship can be very effective in communicating more information to more people who can then advocate for social change.

In other words, Tang and his team have put hard numbers behind what African Americans in Austin have known for decades: that the combined effects of historical racial segregation and current gentrification have led to their displacement from the city. “Our research isn’t revelatory, but only an affirmation of the local knowledge and grounded theory of those who have experienced these issues directly,” he says. He elaborates on this point in his interview with Life of the Mind, referring to himself as just “some guy from UT carrying some numbers and saying, here they are” and with those numbers spurring a new level of surprise that shouldn’t have been. “It is, to me, kind of sad that it’s a UT professor to finally get people to listen, but that’s the way it works, I guess.”

In addition to continuing work in the community, Tang and his team are about to release a companion report to “Those Who Left,” titled “Those Who Stayed.” This report will be based on the findings from surveys of African American residents who refused to move from their historical neighborhoods in East Austin, or as Tang describes them, those who “decided to weather the gentrification blitz.”

Tang believes projects such as East Avenue are immediately relevant to communities that are dealing every day with problems that scholars are addressing. They exemplify the value of public scholarship — that is, mutually beneficial partnerships between higher education and various groups in the public and private sectors. At the very least, these projects can inspire public discourse that can lead to change. Tang says he has noticed a shift since he arrived several years ago. Once where there was a lack of robust discussion, researchers such as Tang have shed light on Austin’s segregation and have brought it to greater public attention. Additionally, the monthly Front Porch Gatherings sponsored by the Longhorn Center for Community Engagement and organized by the center’s director, Virginia Cumberbatch, and Suchitra V. Gururaj, assistant vice president of the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement, connect the resources of the university with underserved Austin communities to foster long-term collaboration.

Tang notes that Austin’s recently implemented 10-1 plan — in which each of the city’s 10 council members represents a geographic district — has helped to shed light on the issue. “The fact that you have not just people of color but white residents in neighborhoods outside of Central Austin who are also feeling like the city is unaffordable, has shifted the discussion.”

More and more people are talking about issues of economic segregation, racial segregation and inequality, but the question remains: Can these trends be reversed? For that to happen, we need to change our thinking about Austin as even having an east side or a west side. As Dixon explained in an interview for the Homelands series, East Austin is Central Austin, and we all need to think more inclusively about the city and its communities.

Recalling his role in the naming of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard, Dixon says we all need to think more as Dr. King did. To him, “the whole world was the parish.”