Let’s talk about statues, or one statue in particular, and all of the trouble a cold, hard, unfeeling thing can cause.

Imagine you are the president of a very large, prestigious institution, representative of the spirit and aspirations of a region. Your greatest benefactor, a former regent and a veteran, stipulates in his will the plans for a grand war memorial involving a huge arch and several life-size statues of controversial figures. In addition to the amount he will provide for this memorial, he will also include funds that your institution can use for other projects. How do you balance your need for the monetary gift with your responsibility to your institution’s community?

In short, how do you solve a problem like commemoration? This issue has bedeviled University of Texas presidents for a century, yet we still wonder whether we’ve done enough to address the issue, or whether the steps we have taken represent progress.

If you haven’t already guessed, the benefactor described above was Maj. George Washington Littlefield, and the memorial he stipulated eventually became Littlefield Fountain and the array of figures on the South Mall, which until recently included Albert Sidney Johnston, Robert E. Lee, James Stephen Hogg, John H. Reagan, Woodrow Wilson, and — most notoriously — Jefferson Davis.

In spring 2015, student government leaders pushed for the removal of the statue of Jefferson Davis. Their effort gained traction beyond the university, thanks to their use of social media. Posts on Twitter and Facebook linked the statue removal to national events such as the June 2015 killing of nine members of the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, by Dylann Roof. After photos emerged of Roof displaying the Confederate battle flag, a nationwide movement began to rid public buildings of the flag, later widening to include statuary of Confederate heroes.

On the heels of these events, incoming President Gregory L. Fenves met with student leaders and convened a task force charged with not only deciding what to do about Jefferson Davis and his companions, but also how to handle future commemoration on an increasingly diverse campus.

The task force recommended that the statues of Jefferson Davis and Woodrow Wilson be removed and placed in the university’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, an appropriate historical and educational context given that the center holds the papers of Littlefield and those of the statues’ sculptor, Pompeo Coppini, as well as the nation’s third largest collection of resources on American slavery. Additionally, the statue of Davis will be exhibited as part of the From Commemoration to Education exhibit that opened in April at the Briscoe Center.

A Confederacy, a Conflict and a Commission

The first president to face the problem of commemoration was Robert Ernest Vinson (1916-1923), who had to negotiate between dueling benefactors Littlefield and George Washington Brackenridge. Littlefield, a Confederate veteran, wanted the university to become a center for the study of Southern history, thus codifying the Confederacy as an important part of the institution’s history. In 1910, Brackenridge, a Northerner and a Union sympathizer, donated 500 acres along the Colorado River as a larger site for the growing university. Littlefield, whose Victorian home sat across the street from campus, opposed the move and in response commissioned Coppini to design a massive — and, most importantly, immovable — arched gateway to the South Mall.

One would have effectively entered the South when one entered the campus through this portal. Modeled on the University of Virginia and with an inaugural board of regents made up entirely of Confederate officers and diplomats, the Forty Acres was founded as a neo-Confederate enterprise, according to Edmund T. Gordon, chair and associate professor in the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies. It remained as such until at least the 1940s, seeing a grand wizard of the Ku Klux Klan as a regent, operating under legislation that required faculty members to “be in sympathy with Southern political institutions,” and celebrating Thanksgiving Day 1914 with a speech by professor William Simkins titled “Why the Ku Klux Klan” (published in The Alcalde in 1916), in which he described the South coming “into her own” and her policies “dominating the administration of our national government.”

Many people today believe the fountain and statues wholly reflect Littlefield’s intention, but as Littlefield’s health waned, Coppini significantly altered the project. The first thing to go was the arch; Coppini turned it into a fountain, insisting that arches were “reminiscent of the Roman Caesarian age” when empires were “bent on conquering and enslaving other people and reminding them of their yoke.” Coppini also tweaked the narrative surrounding the project, suggesting to Littlefield that the piece become a memorial to the World War and stating that as time goes by, the Civil War will be seen as “a blot on the pages of American history,” and “the Littlefield Memorial will be resented as keeping up the hatred between the Northern and Southern states.” Attempting to show that “all past regional differences have disappeared and we are now one welded nation,” the final plan for the memorial presented the fountain we see today flanked by two obelisks representing the North and the South, topped with “wartime presidents” Wilson and Davis.

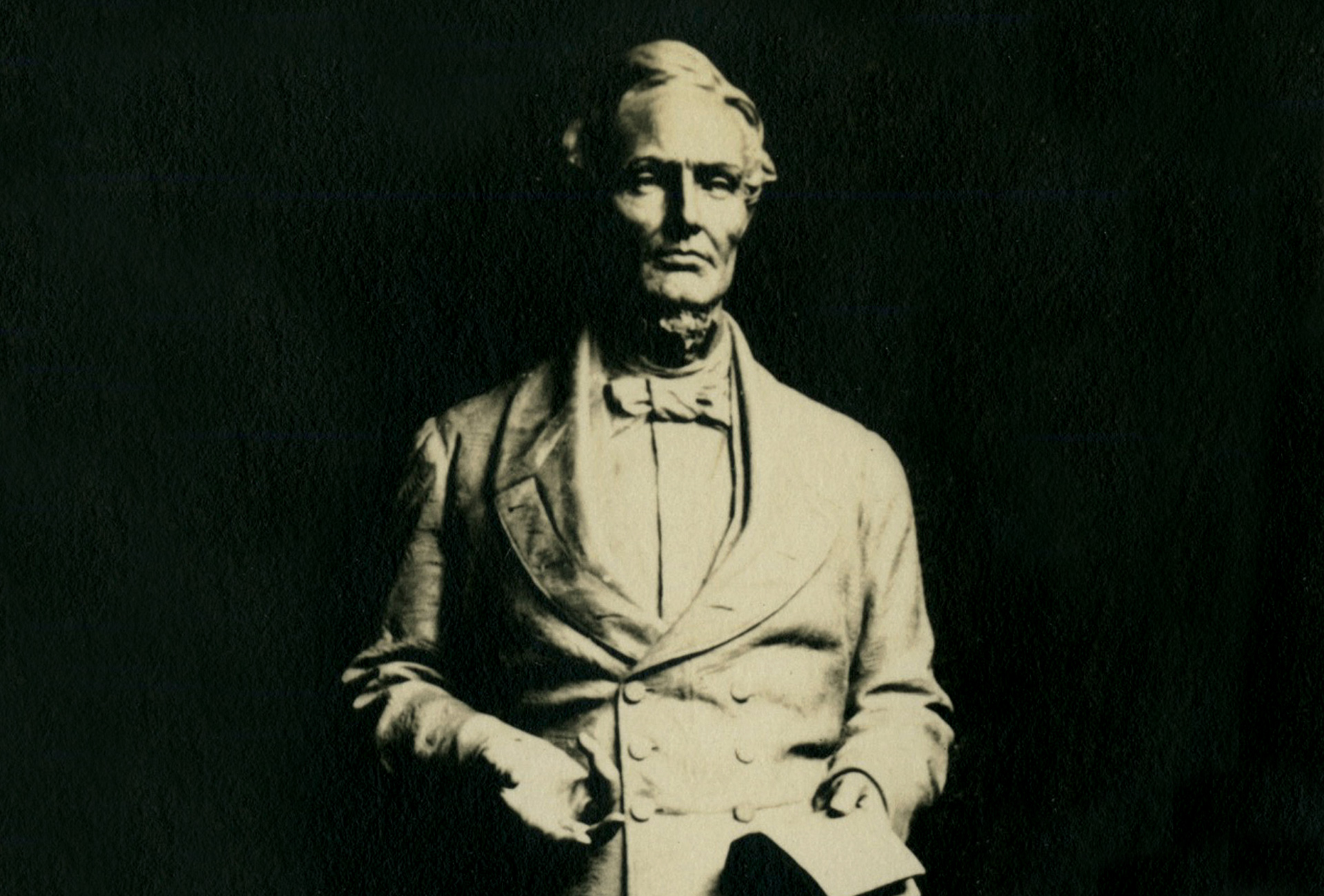

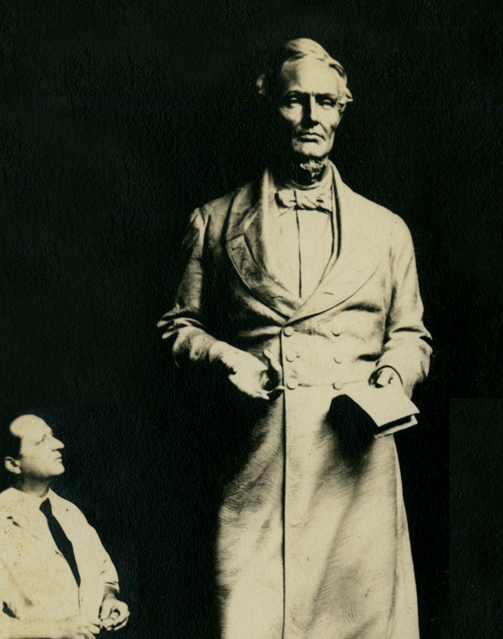

Neither Littlefield nor Coppini were strangers to Confederate memorial building; Littlefield was a member of several Confederate veterans associations, and Coppini was a well-known artist of such memorials, having completed several throughout Texas including one in the town of Paris and one on the grounds of the Capitol. The 1920 Cactus praised him as having a “quick sympathy” with Southern subjects.

The memorial was envisioned during the “neo-Confederate” or “Lost Cause” movement, a period of nostalgia for the social order of the Old South. This movement painted the Confederate cause in the Civil War as an honorable struggle to protect the virtues of the antebellum South, while minimizing or denying the central role of slavery. Although a primarily Southern movement, aspects of Lost Cause philosophy won acceptance in the North and helped reunify American whites across what Coppini once called the “Dixie Line distinction.” In this way the memorial is actually about a reunification of North and South, but through the bonds of white supremacy, reflected in the inscription that was set to the west of the Littlefield Fountain:

To the men and women of the Confederacy who fought with valor and suffered with fortitude that states’ rights be maintained and who, not dismayed by defeat nor discouraged by misrule, builded from the ruins of a devastating war a greater south. And to the men and women of the nation who gave of their possessions and of their lives that free government be made secure to the peoples of the earth this memorial is dedicated.

Gordon says this moment saw the emergence of what was called the “New South,” which called for fuller integration with the United States and was touted by Southern elites such as Littlefield, who sought economic partnerships with Northern capitalists. The New South wasn’t really new to everyone, however, because it involved the continued supremacy of whites over blacks. As Henry W. Grady of the Atlanta Constitution and coiner of the term “New South” said in 1888, “the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race.”

Wilson’s election in 1912 — the first Southerner elected as president since Zachary Taylor in 1848— also led to a sweep of both houses by the Democratic Party, which at that time was aligned with the forces of segregation. In turn, Wilson also oversaw the re-segregation of the federal government. Other men commemorated in the South Mall statuary — John H. Reagan, the postmaster general of the Confederate States who later urged cooperation with the Union; and James Hogg, who was not a Confederate — were both instrumental in the powerful Texas Railroad Commission and therefore key figures in the vision of the New South. The statue of George Washington, featured on the Great Seal of the Confederate States of America, was added in 1955 at the urging of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

‘A Senseless Decoration’

Littlefield died on Nov. 10, 1920, before the construction of the monument could begin. Nonetheless, Coppini completed the statues by 1925 and sent them to Austin to be displayed in the rotunda of the Texas Capitol.

Meanwhile, the university endured battles over campus aesthetics that exhausted the efforts of several architects, who in some cases either completely ignored or altered Coppini’s memorial in their plans. Various aspects of the memorial also fell under scrutiny, most notably its orientation. In all of the original plans, the memorial faced south — ostensibly to provide a grand entrance to campus — but also as a symbolic gesture to the political South. Citing size as the culprit, the regents agreed to move it east, to form a new corridor to the heart of campus. Regent Sam Neathery eventually admitted to The Daily Texan that the regents felt “the arrangement is out of keeping with the times. The work will keep the antagonism of the South against the North before the people of Texas.”

But in the end, the regents honored the donor’s last wishes and hired Philadelphia-based architect Paul Cret to see a south-facing project through to completion. Cret’s vision was purely aesthetic; his goal was to make the university one of the most beautiful in the country, not to tell a story. The Coppini plan, Cret felt, was “a small composition, overcrowded with features and designed without regard for its surroundings.” Consequently, he expanded the footprint of the tableau to extend along the east and west sides of the South Mall, separating the portrait statues from the more allegorical figures in the fountain. Placing the portrait statues along the mall also kept them from obstructing the view of the Main Building, which remained the focal point of the corridor. However, he did not intend to diminish the statues’ representational power, reasoning that “the portrait statues selected by the donor gain in prominence when provided with an individual setting instead of being used as accessories to a fountain design.”

The memorial was finally dedicated on April 29, 1933. Coppini later complained that Cret and the regents had “ruined” the memorial by dispersing the statues, “throwing to the four winds my conception and making of the various pieces of bronze just a senseless decoration of the campus.”

Senseless or not, these “decorations” have vexed university presidents since their dedication, with Davis perennially at the center of the controversy. There were other Confederates in the tableau, but the Davis statue galled because it enjoyed prominence alongside the “other wartime president.” But where was the actual wartime president? “Where are the statues of Lincoln?” asked Otis Singletary, a Texas history professor quoted in a 1950s interview in The Austin American. “I’ve never seen one in the South.”

Changing the Campus Landscape

Fast forward to the 1980s, when President William H. Cunningham (1985-1992) faced a series of racist fraternity incidents that led to protests, a hunger strike and calls for the removal of the statues. The university made changes to how it dealt with racial discrimination and the promotion of multicultural education, but Cunningham refused to remove the Davis statue, telling The Daily Texan it was “a mistake to rewrite history.” Instead, he attempted to create a new historical landscape for campus by announcing plans for a Martin Luther King Jr. statue on the East Mall.

Dedicated in 1999, the King statue was egged on Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2003. In response, President Larry Faulkner (1998-2006) directed a task force to find a more suitable location for historical statues “that are a reminder of our past, but should no longer be prominently positioned on our diverse landscape.” Calling the issue a question of “history, art and architecture,” Faulkner additionally outlined goals for campus statuary that called for the creation of a “hospitable” environment that not only preserved the cultural record and institutional continuity, but also understood history on human terms and maintained artistic integrity. To that last point, he took at face value Coppini’s assertion that the memorial was an allegory about national unity and proposed rearranging the statuary with educational signage to better represent the sculptor’s original intention. The problem, he thought, was that each statue had become “an isolated representation of the depicted individual, with no clear theme underlying the selection of individuals.”

When the King statue was defaced again in 2004, President William Powers Jr. (2006-2015) responded by inviting African American leaders from campus, including Gordon, to talk about the statues and possible options. They decided the statues should be left in place, but new statues should be added to present a more diverse campus landscape. In the years since, the campus has seen the addition of statues honoring César Chávez (2007) and Barbara Jordan (2009).

Which Way to the Future?

And so, after a century, do we finally have resolution? Does recontextualizing the Davis statue as an educational object — “wording him up” in an archive, as senior lecturer in the Department of History Penne Restad refers to it — bind him and prevent him from doing harm? Or does it remove him from a greater conversation about what the statuary say about the university?

You might ask why a supposedly senseless object has so much power in the first place. According to classics professor Karl Galinsky, it might be helpful to think about this issue through the lens of ancient Rome. Because literacy was low in Rome and the rural areas around it, memorialization depended mostly on monuments. They were a visual text that held culture and social memory, and most notably, a record of the maintenance and transition of power. And, different from the archaeological and conservationist perspective we have today, these monuments could be “disposed of, re-placed or replaced” as needs of the culture changed. Thus memorials, as the physical manifestation of memories, have a dual function in that they recall a certain event, while at the same time both shaping and making way for the future. “In sum, what we can learn from Roman history is the traditional freedom to redispose such statues as the culture moves on,” Galinsky says.

In his note to the 2015 task force, Gordon wrote that “history is not innocent; it is the living foundation for the present.” In this case, the Confederate statues serve as powerful symbols of the racism, militarism and gender disparity that are prevalent in the built landscape of the university and which continue to structure the present. Because of their role, he believes the statues should stay in place, but with an effective educational apparatus, to serve as a “Scarlet Letter” on the university, reminding us of past failings and compelling us toward a more equitable future. According to Gordon, removing the Davis and Wilson statues does not erase this history, but instead obscures it, and therefore reduces the possibility for reflection, education, conversation, and ultimately positive change.

“Where are the statues of Lincoln?” asked Otis Singletary, a Texas history professor quoted in a 1950s interview in The Austin American. “I’ve never seen one in the South.”

Restad maintains that the statue removal gave the university an opportunity to show not only where it has been, but where it wants to go. To this end, the task force also expressed that memorials should balance history by “telling multiple sides of the story from a variety of perspectives,” including enslaved people, Native Americans, Mexican Americans and other groups and individuals “who made their mark on UT Austin’s history.” Gordon agrees that the presence of statues of people of color is a step in the right direction, especially as they exist in opposition to the Confederate statues, and therefore bring the history of the university into greater focus.

But is any attempt to rewrite the landscape of campus a long-term solution, or is it a temporary palliative? Professor John Morán González, director of the Center for Mexican American Studies, fears it is a kind of “Band-Aid,” and suggests the naming of more buildings, classrooms and open spaces after prominent Latinos would help “indicate a permanent and historical anchoring to the mission of the university.” González also suggests adding Latino representation through public art and bilingual signage. “When we ask, ‘who is our public?’ we have to ask how language choices indicate inclusion or exclusion within that concept.”

As Gregory J. Vincent, vice president for Diversity and Community Engagement says, the recommendations of the task force should not be seen as a “cure-all for campus,” given our ever-changing culture. “Our current climate is undoubtedly one of great passion and emotion, regardless of which side of the aisle your politics fall. But what I have seen on this campus more than ever has been an increased level of engagement by our students, faculty and staff. It has been their debate that defines the greatness of our university, and it has been uplifting to see our campus united by our shared experiences and beliefs, rather than be pulled apart by our differences.”

In the end, the university can only go so far to overcome a controversial past; what we need is what Gordon calls “informed and purposeful systemic change.” And while a university president can lead us, we all need to be involved in the work to create the university we want to be.

In partnership with The Humanities Media Project.