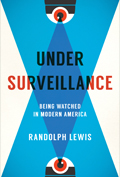

“Even a strutting exhibitionist has something to hide: certain diary entries, genetic predispositions, financial mistakes, medical crises, teenage embarrassments, antisocial compulsions, sexual fantasies, radical dreams,” writes Randolph Lewis. “We all have something that we want to shield from public view. The real question is: Who gets to pull the curtains? And increasingly: How will we know when they are really closed?”

Why worry about surveillance if I have nothing to hide? This has become one of the most disingenuous phrases in the English language, according to Lewis, an American studies professor and author of the new book, Under Surveillance: Being Watched in Modern America (University of Texas Press). It is a phrase often spoken with a privileged voice, but spoken by people who are rarely prepared for someone to start digging into every forgotten email or ill-considered social media post.

Surveillance has become engrained in governance, business, social life and even churches, but well-intentioned technology can have unexpected aftershocks that far exceed their intended purpose. UT Austin professors are beginning a much-needed conversation on how we relate to surveillance emotionally and ethically, and what that means for our security and our way of life.

SOMEONE TO WATCH OVER ME?

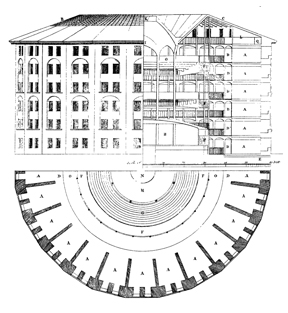

Imagine a “state of permanent visibility” in which your every action may be recorded and each step you take leaves a digital footprint, rendering you utterly predictable.

Frantz Fanon, a Martinique-born psychiatrist, philosopher and writer, described the emotional and physical response to constant monitoring as: “nervous tensions, insomnia, fatigue, accidents, lightheadedness and less control over reflexes.”

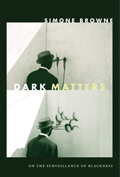

Fanon was a jumping-off point for Simone Browne’s research for her book, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press) when her requests for information on Fanon to the FBI and CIA were met with a response that neither confirmed nor denied the existence of files. She was particularly interested in Fanon’s travels to the United States during 1961 to receive treatment for myeloid leukemia; he would die that year at the age of 36.

“Fanon was this critical theorist, someone who actively participated in anti-colonial projects; to think that his death in the U.S. is something that is still under this Glomar response (can neither confirm nor deny) was a spark to think about how blackness itself is redaction — sometimes you see these FBI documents blacked out,” says Browne, a sociologist and an associate professor of African and African diaspora studies. “These important parts gave me a way to think about how in the study of surveillance a lot of important parts about black history and presence get redacted, too.”

When we think about surveillance, we often imagine it in the abstract, like “Big Brother” or a shadowy government agency — something out of a Tom Clancy novel — but surveillance can be felt at a very real and intimate level.

For example, Browne points to the ways a person might monitor a spouse or partner, check into their phone receipts, track their everyday movements by whom they’ve been calling or texting. It might not be a hacker or a government wiretap, but it is nevertheless a type of surveillance.

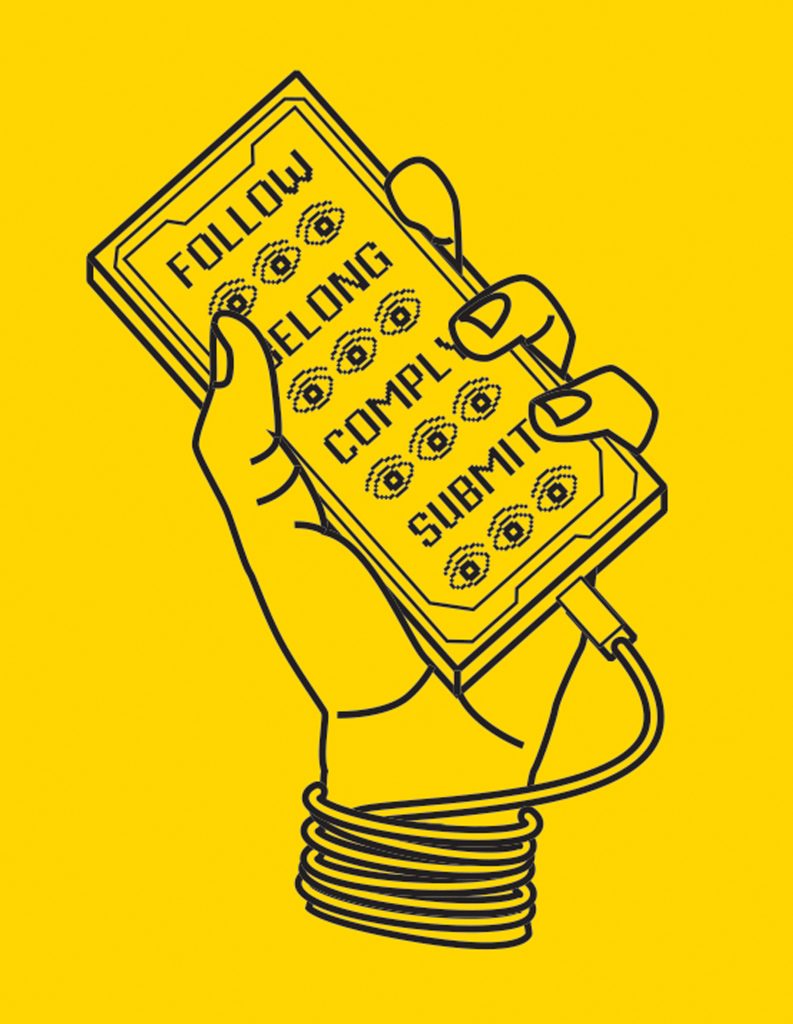

“My fear is that [digital natives] will just accommodate themselves to it because it’s easier, and because we are seduced into doing it by corporations that get so much data from us, and what we get is a free game, a free app, a social network.”

Randolph Lewis

Architectural design can also lend a watchful eye to surveillance culture. Jeremy Bentham, the early 19th-century reformer known for his controversial designs for English prisons, located a nearly invisible watcher at the center of a circular prison. The design provided the mental restraint that comes from the assumption of constant monitoring — much like social media sites do today.

“You can even think about something like a public bathroom,” Browne says. “A lot of times when you go into public bathrooms the door doesn’t reach all the way to the ground, there is some space between the door, so you can actually see people walking. A lot of that could be about controlling who’s in the bathroom. Bathrooms, as we know, are quite a contested space.”

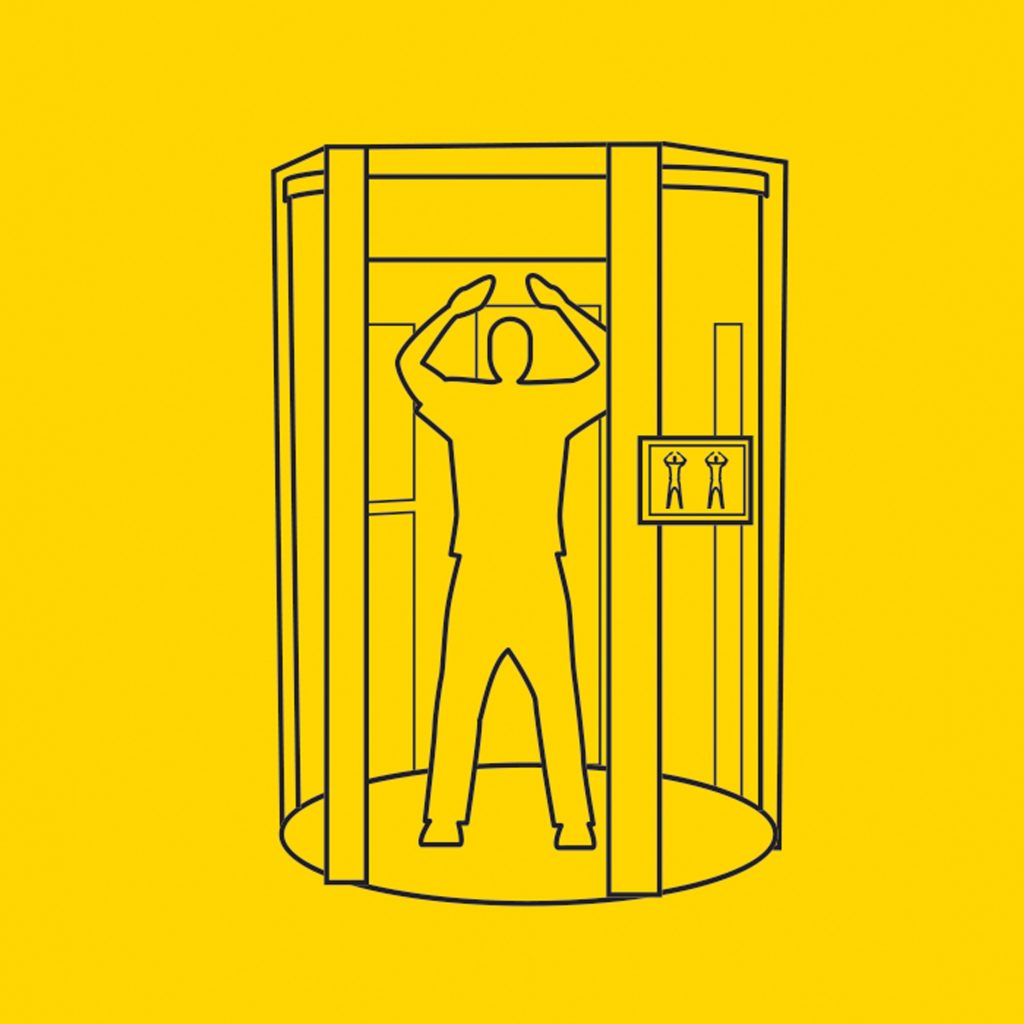

Physical spaces such as airports can be an especially anxiety-filled. Browne describes it as a type of security theater or performance that is dependent on anxiety and compliance. It’s the notion that people being uncomfortable would betray some type of tell if they were “up to no good,” Browne says. It’s already an anxiety-filled space because you might be subjected to a search based on your hair, gender or self-presentation. This security theater is probably most pronounced in the TSA check-in line, where “safe” and “unsafe” areas are in close proximity. “Anyone can stand up there really,” Browne says. “To think about the TSA checkpoint being an unsafe place, and the idea that right next to it is safe — the space where the security is happening and we are taking out our liquids and taking off our belts.”

Lewis points out that it may be no coincidence that anxiety rates in America are at historical highs. When we are moving around airports or city streets, there’s a self-consciousness that can be overwhelming, especially if you’re already an anxious person, he says. Surveillance has even encroached upon our natural landscape, taking with it those feelings of escape and tranquility.

“Wilderness is always a little bit of a fantasy,” Lewis says. “We’re going to be off the grid, but it’s an important fantasy in America to be unobserved and truly alone in nature, and that’s going to become impossible as drones are flying overhead.”

“We are losing our liberty and important forms of dignity that can only exist when we are able to be truly alone, at least for a moment,” he says.

GROWING UP OBSERVED

In the 1960s, the social critic Paul Goodman published Growing Up Absurd: Problems of Youth in the Organized Society, a grim look at the homogenized mass culture for those who had grown up during the Eisenhower years, but Lewis says today our children are reared in an additional layer of absurdity: the controlling gaze of the parent, school and state, which creates a culture of almost constant monitoring.

“Rather than growing up absurd, we are growing up observed …,” Lewis writes. “And this constant emphasis on control, predictability and security seems to have a perverse byproduct: The more we press for a deep and lasting sense of security, the more we are miserably insecure.”

Surveillance has even crept into the workplace and home. Hotel maids may be monitored for maximum efficiency, call center operators may be listened to for an appropriate customer service tone, and nannies watched with suspicion via nanny cam.

“One of the sad things about this type of domestic surveillance is that we constantly hear these horror stories about nannies — working class, often people of color — my mom was a nanny, so I’m really sensitive to this, I guess — they are held up like the demon in so many news stories,” Lewis says. “They are going to hurt your child; they are going to shake the baby — where statistically there’s no evidence that nannies pose any danger to children any more than the rest of the population. It creates another level of social disconnection, paranoia and fear around something that is already emotionally fraught, which is letting someone else take care of your child.”

“It’s kind of the regulatory Wild West where there’s this data hunger.”

Sarah Brayne

There is a crippling self-consciousness that can come from feeling monitored so closely and invasively, but what will the next generation’s response to surveillance technologies be? The answer may lie in our biographies, particularly in aspects of our identities in regard to empowerment, autonomy, respect and vulnerability.

“I think that I’m in a transitional generation where this feels really foreign and toxic to me to live in the increasingly surveilled mode,” Lewis says. “The real question is for digital natives who are 15 years old like my daughter. Will it seem strange to them or just part of a world they’ve just grown up in? And we don’t really know the answers except for anecdotally.

“My fear is that they will just accommodate themselves to it because it’s easier, and because we are seduced into doing it by corporations that get so much data from us, and what we get is a free game, a free app, a social network,” Lewis says.

DATA HUNGER

A November 2014 Pew Research survey revealed 91 percent of Americans “believe that consumers have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by companies.” Although consumers seem to dislike this, there seems to be a disconnect between their feelings and actions.

The brokering of private data is a multibillion dollar industry. Data has become capital in the Digital Age, and so this huge industry has emerged to sell, share, trade and even rent your data.

“We normally think about consent at the point of data collection, like ‘Yes I’m consenting to give this contact lens company my information or yes, I’m consenting to give my phone number to Pizza Hut when I call and order a pizza,’” says Sarah Brayne, assistant professor of sociology and a Population Research Center research associate. “But with this repurposing of data, or what some people call ‘data creep’ or ‘function creep’ — the idea that data originally collected for one purpose is then used for another — is rendering this concept of consent somewhat anachronistic, and it doesn’t really fit well with how data is used now.”

Privacy laws usually relate to the point of data collection, but not “function creep” or repurposing of data that may be collected with no expressed purpose.

“It’s kind of the regulatory Wild West where there’s this data hunger; let’s just collect all the possible information we can, and then we’ll try machine learning. We’ll try seeing if we can learn anything from this data,” Brayne says.

“Data collection doesn’t always have to have malintent either,” she adds. “A lot of data integration is originally done under this welfarist ideology of service delivery. Like electronic medical records — let’s improve prescription drugs and care coordination, that kind of thing. But once data exists, it can be repurposed, and so the harder edge of social control can come into the picture.”

It’s difficult to change habits and the conveniences we become accustomed to, even when the safeguards are not in place.

“I wish Equifax and these other breaches would provoke some type outrage that lasted for more than a week,” Lewis says. “One company after another gets hacked, and we lose all of this data, and there’s not real accountability or consumer protection. I think that this is the most maddening part of this, the unknowability and unaccountability.

“We’ve created this incredible machinery of surveillance, and if you trust who’s got the keys to the system, OK. Fine. But what happens if it’s in the hands of someone you don’t trust?” Lewis asks. “We need to figure out a way to have a really mature conversation about privacy in the Digital Age,” Lewis adds. “But my cynicism comes in where I don’t think we have the political leadership or the cultural maturity to have that conversation. It’s a really hard one because we might have to give up some of the fun things about surveillance culture.”

FUNOPTICON

In an age when we bring our smartphones almost everywhere with constant connectivity, ordinary people find themselves encouraged to play along with surveillance practices, and most are happy to oblige in the name of convenience, connection or fun. We, in part, share in the surveillance burden.

“The implication is fascinating: The world won’t get a radical makeover when surveillance becomes omnipresent, woven deep into our buildings and bodies, but instead it will look reassuringly familiar to us,” Lewis writes. “The new Panopticon will have Wi-Fi, cappuccino and vegetarian options. It will utilize the language of choice, freedom and pleasure. It will speak casually about freedom and dignity. It will make us laugh and feel connected with a lightness of spirit that seems, at least on its bright, shiny surface, very far from the world of Bentham, Orwell and Foucault. It will make surveillance seem cool.”

However, some of that convenience and entertainment may come at the cost of your privacy, Lewis writes in a chapter devoted to what he calls the “Funopticon.” Lewis shares examples such as the Roomba vacuum cleaner that maps your home to know your furniture’s locations for cleaning purposes, but then the company sells that information to third parties who may then send you targeted ads; or the Samsung television introduced a few years ago that used voice commands and recorded every conversation in the house, a practice the company has since discontinued.

Uploading your image on Snapchat with bunny ear filters may sound fun in the moment, but you should also consider that you’ve now given an entity, Snapchat, access to your biometric measurements.

Simone Browne

It’s become increasingly difficult to manage our data footprint, especially our digital presence on social media. Employers can already search job candidates’ social media presence to gain insights into the candidates and their friends. Insurance companies have even used Facebook to deny claims.

“If you’re not on Facebook, your friends may put you there in group shots, so it comes back to questions of consent and access, and can we truly even opt out of some of these surveillance sites because for many people, a site like Facebook — I think it has close to over a billion users now — it’s something they see as a necessity, whether it’s for news or connection to family and friends or seeing pictures of cute cats,” Browne says.

Uploading your image on Snapchat with bunny ear filters may sound fun in the moment, but Browne says you should also consider that you’ve now given an entity, Snapchat, access to your biometric measurements.

Often, we don’t understand how the body is made into data, or what our rights are to our own body data. Browne says one possible way to improve our understanding would be a push for shorter user agreements in plain and easy to understand language. Browne asks her students to think about what happens to this data. How long is it stored? How is it shared?

“It’s not only about understanding the human body, but the notion of how much can we refuse to have our body turned into data,” Browne says. “And often the question is no. If you need to get a green card, you have to give your fingerprints or you have to give your face print, and some places you have to go closer with your iris. So, there are questions of what are our rights of refusal and ownership. So who owns that data? Information that is derived from the human body, is that our intellectual property or that of the social media site, the government or the other entity that has this information?”

BIOMETRIC SURVEILLANCE

Biometrics in its simplest form is a means of using the human body as identification.

Browne recalls working on her dissertation about Canada/U.S. border security when the permanent resident card — considered to be one of the most secure documents due to its use of biometric information — was issued after 9/11. She says that got her interested not only in the ways that surveillance is used at the site of the human body, but also who is targeted and even opting in to these types of technologies.

Browne cites a U.S. company in Wisconsin that uses radio frequency identification (RDIF) chips that are embedded under the skin. “It’s the idea of being cool and on the cusp of using medical-grade radio frequency identification chips that you can use to open a door. They call them biohackers … But the idea that a company encouraged their employees — I use the word encouraged lightly — to sign in or out like a punch clock.

“Your employer could track more about you. What happens if you leave that company in Wisconsin?” Browne asks. “What happens if (the chip) migrates in your body and it can’t be removed or it calcifies and hardens? Those are also concerns.”

RDIF chips are also being used at some exclusive hotel resorts. Browne mentions an example in Ibiza, Spain, and there are nightclubs offering access to VIP areas and using the chip to serve as a debit account. Unlike people who don’t have the right to refuse (those who are imprisoned or even children), this clientele wants to be the first to try something cutting edge.

The idea of biometric surveillance is nothing new. Browne’s book gave her the opportunity to look at how our history informs our present.

“I looked at branding of enslaved people as a form of marking the body as a site of surveillance,” Browne says. She also looked at how runaway notices would include not only physical descriptions, but what the runaways took with them, what they wore and the languages they spoke.

Browne researched The Book of Negroes, a record of 3,000 formerly enslaved black people who escaped to the British lines during the American Revolution and one of the first large-scale uses of the body as a means of identification and tracking by the state. The British ledger included name, place of birth and physical description.

“Whether someone had lost an eye or they had pockmarks, these types of ways of identifying a person became important because claims might be made of these people who were to be free, but there were others who demanded they were to be property,” Browne says. In essence, The Book of Negroes is a story about the regulation of mobility through biometric surveillance.

LUMINOSITY

Lantern laws in 18th-century New York City mandated that enslaved people carry lighted candles as they moved about the city after dark, writes Browne. Luminosity sought to keep the black, the mixed-race and the indigenous body in a state of permanent illumination, thus regulating people’s mobility, she explains.

“Lantern laws made the lit candle a supervisory device — any unattended slave was mandated to carry one — and part of the legal framework that marked black, mixed-race and indigenous people as security risks in need of supervision after dark,” Browne writes.

“We live in a messy social world, and so data is also a messy reflection of that.”

Sarah Brayne

“That was still a technology at the time, but the idea was that these human beings became part of the city’s lighting infrastructure in some way,” Browne says. “It was not only about surveillance — the individuals who were mandated to carry these lanterns, but it was about lighting up the city in some way for other people who were walking. And I think you still see the ways that certain humans get made into technology in our presence.”

Browne recalls as an example the 2012 South by Southwest Festival, when BBH Labs hired homeless people to wear hardware that made them Wi-Fi hotspots, which some people criticized as dehumanizing. The homeless participants became part of the Wi-Fi infrastructure, wearing T-shirts that said, “Hi, I’m a 4G Hotspot.” Another example is the 2010 city code in Tampa, Florida, requiring roadside solicitors to wear reflective vests or risk a citation from the police.

BIG DATA POLICING

Brayne’s research, published in the American Sociological Review, examined for the first time how adopting big data analytics both amplifies and transforms police surveillance practices. Brayne interviewed and observed 75 police officers and civilian employees of the Los Angeles Police Department — a pioneer in data analytic policing — to identify key ways law enforcement has implemented in-house and privately purchased data on individuals to assess criminal risks, predict crime and surveil communities.

“I think that what’s really important is that it’s not just one new surveillance technology that’s transformative, but rather, it’s this combinatorial power of using different things in conjunction with one another that grants authorities a level of insight into individuals’ lives that previously would have required a warrant or one-on-one surveillance,” Brayne says.

Big data supplements officers’ discretion with algorithm-based, quantified criminal risk assessments. For example, in some divisions, an individual’s criminal risk is measured using point values based on violent criminal history, arrests, parole or probation statuses and police stops. People with high point values are more likely to be stopped by police, thus adding another point to their record.

“When you start to codify or bake in police practices as objective crime data, you sort of get into this feedback loop or self-fulfilling prophecy,” Brayne says. “It puts individuals who are already under suspicion under new and deeper and quantified forms of surveillance, masked by objectivity or as one officer described it: ‘just math.’

“You have to believe that the data is perfect, and it’s not,” Brayne adds. “We live in a messy social world, and so data is also a messy reflection of that.”

Brayne says she definitely thinks law enforcement and other surveilling agents should use emergent technologies to improve service delivery, reduce crime and focus resources. However, she does think they can improve their practices by rolling out things more slowly, more thoughtfully and more systematically to gain empirical insights about best practices.

“While people in managerial roles tended to love it, line officers felt like it was a means by which they came under increased surveillance themselves,” Brayne says. “There is a lot of distrust among officers about what is actually happening.”

THE BUSINESS OF INSECURITY

Some U.S. churches have begun to invest in surveillance technologies with security teams and threat detection at the door. Lewis focused his research on smaller and mid-sized suburban churches.

“It’s just really strange to be in a church where there is a crucifix and above that a camera and you start to wonder, which one really has control here in some symbolic sense?” Lewis says. Lewis attended a surveillance trade show at the Javits Convention Center in New York — filled with spy gadgets, cameras and sensors galore — to try to gain a better understanding of what is motivating some churches to make such a large investment in security.

“The market uses emotions to sell things and doesn’t give any consideration to ethics or even efficacy,” Lewis says. “That really blew my mind because I thought ‘Well, you can’t sell this million-dollar system without saying: Here’s the evidence that it works,’ but you can.”

RECOMMENDED READING:

Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness

Duke University Press, Oct. 2015

By Simone Browne, associate professor,

Departments of African and African Diaspora Studies and Sociology

Under Surveillance: Being Watched in Modern America

University of Texas Press, Nov. 2017

By Randolph Lewis, professor,

Department of American Studies