When it comes to staging a revolution, timing is everything.

In 1959 an island nation of 7 million revolted against its U.S.-backed dictator, and with its subsequent export of revolution to Latin America became a major driver of U.S. foreign policy during the Cold War.

In a story as compelling as it is complex, Professor Jonathan Brown’s new book, Cuba’s Revolutionary World, shows us why this one revolution — at a particular time in history — succeeded where many others had failed.

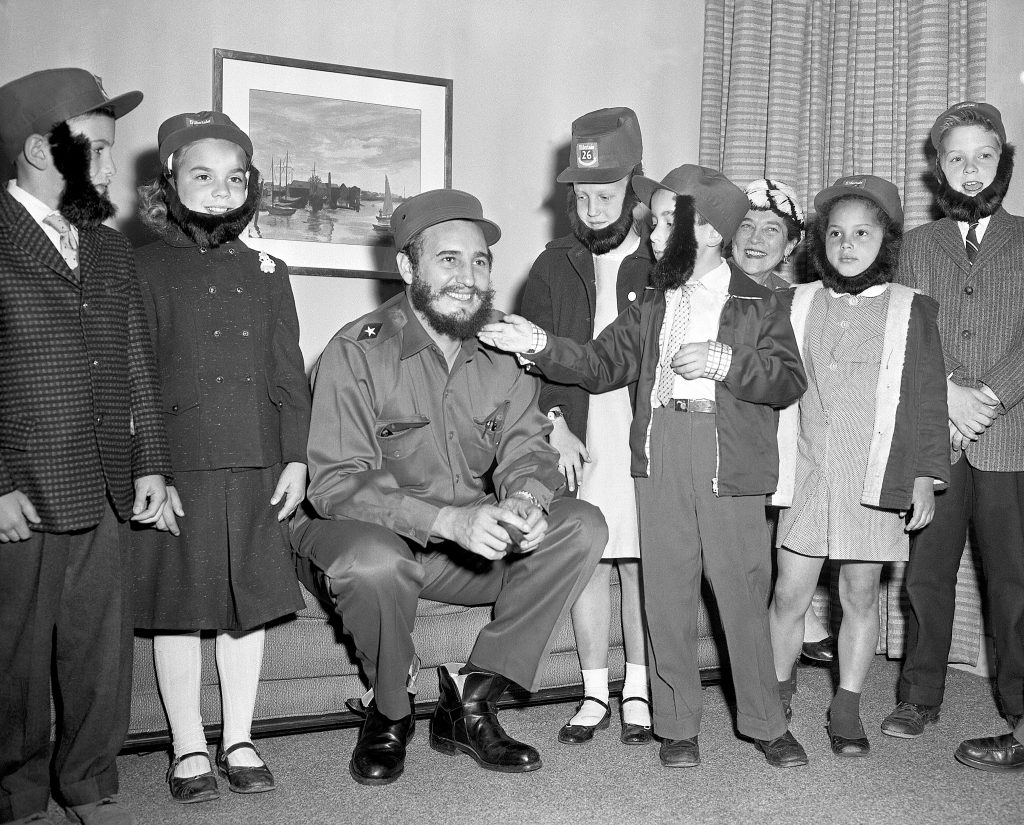

When Fidel Castro’s rebel forces seized control of Cuba on Jan. 1, 1959, their success in maintaining and building support among the Cuban people was fueled in part by the counterrevolutionary actions of the United States, which at the time saw much of the world through the lens of its rivalry with the Soviet Union.

“If the Cuban Revolution happened in 1949 rather than in ’59, it would have been completely different because of the international constellation of countries and their competition at the time,” says Brown, who teaches in the nation’s top-ranked Latin American History program in UT Austin’s Department of History.

The Cuban Revolution occurred at a time when a political tactician like Castro — who was a voracious reader and student of the French Revolution — seized the historical moment and exploited tensions between the superpowers, ultimately turning to the Soviets and Marxist-Leninism more for pragmatic than ideological reasons.

“The Cuban revolution in its origins wasn’t about Marxist-Leninism, it was more about nationalism,” says Brown. However, Castro’s fellow revolutionary, the Argentinian Ernesto “Che” Guevara, was committed to socialism — and to spreading the socialist revolution — from the very start.

“Fidel, after all, faced the practical concerns of running a country. But he never parted ways with Che, even when Che went to Latin America by himself [to export the revolution],” says Brown. “Their partnership was pretty important. Che kept Fidel grounded in the revolutionary ideology and the revolutionary pursuit.

“But neither Che nor Raúl [Castro] had Fidel’s personality or political skills. He was probably one of the greatest politicians of the 20th century for good or for ill, because he was so effective,” says Brown. “It’s hard to believe that the Cuban Revolution of 1959 could have produced another leader like him … if Fidel had taken a bullet on the last day of 1958, would history be the same?”

Within the context of the Cold War, Cuba’s export of revolution vastly disrupted the status quo in the Western Hemisphere, leading to a “secret war” with the U.S. that was largely conducted by the CIA. Ironically for the U.S. — a country that promoted democracy around the world — this secret war actually led to the decline of democracy in Latin America because the U.S. felt compelled to prop up anti- Castro leaders, even if they were dictators. In essence, Cuba exported both its revolution and counterrevolution.

“How many dictators do you know who can retire in their home country, and die peacefully in bed?”

Jonathan C. Brown

“Any way you look at it, there is a lot of irony in the Cuban Revolution,” says Brown, who writes that “[Washington’s] opposition to Cuba trumped all other policies for Latin America. As a result, generals ruled Brazil for 21 years and Argentina for most of the 30 years after the fall of [Juan] Perón in 1955 … By 1976 a majority of Latin Americans lived under military rule, as opposed to 1958, when only a small minority did.

“The U.S. support of counterinsurgencies in Latin America became something like a game with no end point,” observes Brown. “The CIA didn’t want to show that its hand was behind it all — but they did want to continue to harass Castro.”

But Cuba also effectively played the game with the U.S. and with the Soviets, who like the Americans were not keen on Cuba’s export of revolution. In fact, the Soviets weren’t all that interested in Cuba until a change in leadership made it attractive to Joseph Stalin’s successor, Nikita Khrushchev.

“Stalin would never have gotten involved in the Caribbean, but it just so happened that Khrushchev was looking for a big victory somewhere outside of his country, and Cuba was it,” says Brown. “The official doctrine from Khrushchev to [Leonid] Brezhnev was that they wanted to compete peacefully with the United States and Western Europe, and they did not want to risk nuclear war. But Cuba wanted to go out and spread the revolution to the rest of Latin America, and they got away with it. That’s the amazing thing. And still the Soviets kept giving them arms and economic aid.”

Although Cuba’s adventures abroad played an outsized role in Cold War politics, Che Guevara’s dream of exporting revolution to countries in Latin America and Africa was mostly unsuccessful.

One exception was Panama, which had sought for years to gain control of the U.S.-occupied Canal Zone that bisected the small country. In 1959, eighty armed Cubans led by two Panamanians assaulted Panama’s small Atlantic port, Nombre de Dios. Perhaps the assault helped to “rile up” a few Panamanians, but Brown notes they already had inspiration in the 1956 anti-imperialist uprising at the Suez Canal.

If anything, it was U.S. intransigence that fueled the ire of Panama’s citizens and leaders. Brown writes that during a time of strong anti-communism in the U.S., “Castro always popped up as the cause of the troubles over the Panama Canal.” When the Americans showed no interest in renegotiating the canal treaty, Panama’s de facto dictator Omar Torrijos reached out to Cuba and sought assistance from the newly formed Non-Aligned Movement, created by Castro to ensure “the national independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of non-aligned countries” in their struggle against imperialism.

Brown saw first-hand the mood in Panama, where he served as a military officer in the Canal Zone in the late 1960s.

“I arrived in Panama about three or four weeks after Torrijos made a coup d’état. He did not become the right-wing dictator the Americans usually put up with. He became a reformer,” says Brown. “It was the inability of politicians in Washington to fashion an intelligent policy that led directly to the coup by Torrijos, who would eventually convince the Americans to give up control of canal operations and the Canal Zone itself. He probably would not have been able to do that if it hadn’t been for Fidel Castro.”

Although Cuba had less success in exporting revolution to other countries, this aggressive stance did buy it a measure of security.

“You look at the French Revolution, the Iranian Revolution, the Russian Revolution — they wanted to inspire revolutions in other countries to bring safety to themselves, and they knew that their neighbors were going to hate them because they had introduced a new model of development to the region,” says Brown. “So, in order to sustain the revolution over the long term, the revolutionary leader uses aggressive foreign policy to continue to mobilize people, and the leader gives each new generation a revolutionary mission.”

Cuba remains the only country in Latin America that has successfully defied the United States and cut off all relations to the country. And up until his death in 2016, Castro was probably the most successful nationalist dictator in the world. Asks Brown: “How many dictators do you know who can retire in their home country and die peacefully in bed?”

Fidel, his brother Raúl, and Che were successful in equalizing society and destroying the class system in Cuba, notes Brown, but now that Cuba is changing back into a more worldly, globalized economy, the class system is coming back, favoring white Cubans who have relatives in Miami.

Despite the changes in Cuban society, including the relaxing of economic restrictions, strong opposition remains to normalizing relations with Cuba, particularly from the Cuban-American community in Miami. According to Brown, that too has deep historical roots.

“Castro’s revolution was a middle-class revolution — Fidel himself was from that background. They were educated people,” says Brown. “But the Cuban middle class was also a historically divided class. Long before the revolution there were great sectarian divides. The middle class could not unite on any political objective. And that was true from 1902 when they were allowed to become independent from the U.S. up until 1959, and that’s why only a strongman could stay in power and unite the country. It was the middle class that moved to Miami.”

Brown notes that those who arrived in Miami first were the most conservative members of Cuba’s middle class, many of them supporters of deposed dictator Fulgencio Batista. And because they were there first, they still have a lot of control over money and politics in Miami’s Cuban community, as well as over Washington’s stance toward the island nation.

“Our foreign policy toward Cuba depends upon presidential electioneering, and that’s really sad. Fidel is still influencing the United States … from the grave,” Brown says. “You can never expect intelligent foreign policies to come from presidential elections, because every president will be blocked from creating new policies for unusual situations in the world. The electorate always goes for strength first. All during the Cold War we confused nationalism with communism and treated both the same — with hostility. And it didn’t matter if the nationalist was a dictator or a democratic leader elected by his own people.”

Brown says he believes Cuba will remain a communist nation “as far into the future as I can see. It will remain communist like China has remained communist. But economic restructuring, social change, those may be allowed to proceed. But the Communist Party is not going to give up without a fight.”

He says Cuba’s communist leaders can persist because they have a “safety valve” in the U.S. “Because the country is so close to the United States, anybody who is politically upset with the Communist Party can always leave and join the people in Miami and continue to live a Cuban life.”

As for future relations with Cuba, Brown says it is important for Americans to remember one thing: “The Cubans will always be Cubans. And they’re not Russians.”