Japanese writer Yukio Mishima has long been a favorite of the international press. In a 1966 edition of Life magazine, he was called “Japan’s Dynamo of Letters” and “the Japanese Hemingway.” Appearing on the cover of The New York Times Magazine in August 1970, he was dubbed “Japan’s Renaissance Man.”

The prolific writer was also an occasional film actor and director, singer, bodybuilder and avid martial arts practitioner, and The New York Times cover depicted him dressed in a white kendo jacket and hakama, wielding a katana sword.

Less than four months later, he was dead.

He had committed ritual seppuku, what’s more familiarly known as hara-kiri in the West: self-disembowelment by a short sword followed by decapitation with a long sword at the hands of a trusted acquaintance.

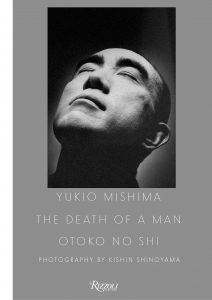

A half-century later, Yukio Mishima’s dramatic final act continues to puzzle and haunt. No less puzzling or haunting is a newly published photo collection, which has appeared in English as “Yukio Mishima: The Death of a Man” and in Japanese as “Otoko No Shi.”

Made by Kishin Shinoyama, one of Japan’s leading photographers since the 1960s, and choreographed by Mishima in the months leading up to his death, the photos depict the now long-dead Mishima dying over and over again.

I’m currently at work on a book titled “Scripting Suicide in Modern Japan” that explores dozens of Japanese writers who, like Mishima, scripted their suicides into their work – from a 16-year-old university prep student who etched a final philosophical poem, “Thoughts at the Precipice,” into a tree at the head of a waterfall before leaping to his death in 1903, to the cult manga artist Yamada Hanako, who eerily prefigured her own leap from the roof of a Tokyo high-rise apartment in 1992 in a comic panel.

Their acts raise the question of how people can fashion and curate their own self-image – in life and in death. They’re a reminder that the traces of the dead linger on unexpectedly, sometimes even by the design of those who have left us behind.

Yet none has confounded more than Mishima.

Right-wing renaissance man

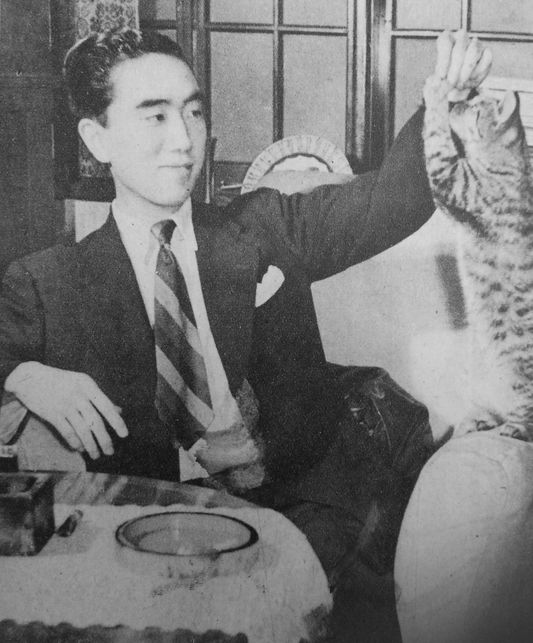

Mishima came early to fame as a literary writer, publishing his first stories as a precocious teenager in 1941 and catapulting to fame with the 1949 semi-autobiographical novel “Confessions of a Mask.” Considered the main contender to become the first Japanese author to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, he was beaten out in 1968 by his mentor, Yasunari Kawabata. Never content to confine himself to any single box, Mishima also wrote poetry, modern Noh theater and Kabuki plays, sci-fi, pulp noir and volumes of cultural criticism.

Nor was he content to confine himself to the literary field. Over the course of the 1960s, he became an increasingly vocal right-wing advocate for restoring political power to the emperor and to the Japanese military. After the country’s defeat in World War II, both institutions, he lamented, had been rendered impotent by a U.S.-imposed postwar constitution that reduced the emperor to a symbolic figurehead and renounced Japan’s right to wage war.

On Nov. 25, 1970, after months of meticulous planning, Mishima and four members of his self-styled militia, the Shield Society, attempted a coup by taking a hostage at Japan’s military headquarters. Mishima delivered a rousing speech to the young cadets but was unable to gain their respect or support. Seemingly anticipating the plot’s ultimate failure, he then committed seppuku. His alleged male lover, Shield Society member Masakatsu Morita, followed suit.

Ever fearful of aging and living on past his prime, he had taken his life at age 45, when he was at his peak physically and creatively. Afterward, Mishima again appeared in Life magazine.

This time, it was a photo of his severed head propped up beside Morita’s.

Trying to explain the inexplicable

Mishima’s decision to commit suicide in this way has fueled speculation over his motives. Like a Rorschach test, the incident offers limitless interpretations that can suit almost any agenda. On and on goes the search for a reason that might explain this inexplicable act.

Seppuku had long been an exclusive right of the samurai warrior caste, but both the samurai and their exclusive mode of dying were abolished as part of a push by Japan’s leaders to modernize the country in the late 19th century.

Some interpreted his suicide in cultural and political terms. By committing to an anachronistic method of dying long outlawed by the authorities, he sought to revive the nation’s samurai spirit. It was a call to throw off the shackles of U.S. imperialism and return to a traditional Japan.

Others have claimed that his dying in this excruciatingly painful manner – alongside his young male lover – marked the climax of an erotic fixation on death. Some view this in highbrow, philosophical terms, quoting Mishima’s reviews and essays on French philosopher Georges Bataille on the union of Eros and death. Alternatively, lurid tell-all memoirs by his former male lovers reveal his erotic investment in enacting suicide in highly choreographed role play.

Death that deadens in its repetition

What gets buried in these many theories is the profusion of art that Mishima produced as the date of his suicide approached, knowing full well that these works would be consumed in its aftermath.

In “The Savage God,” Al Alvarez’s canonical work about the relationship between suicide and the arts in Western society, he points out how the logic of suicide is, to outsiders, inaccessible, a “closed world.” And in his classic work “On Suicide,” essayist Jean Améry, who survived Auschwitz and one suicide attempt but not his second, suggests it is equally incomprehensible to the person taking his own life, likening it to the feeling of being “surrounded by a thoroughly impenetrable darkness.”

However, with Mishima, this world is far from closed. Instead, it is perhaps all too available, blasted out into the world in multimedia and showing no signs of slowing down even 50 years later.

“The Death of a Man,” published by Rizzoli Press in an English version in September of last year, contains a collection of photos taken by Shinoyama in the weeks before the suicide.

In these images, Mishima appears dead over and over again. In one, he’s dressed as a sailor who’s been whipped to death on board a ship; in another, he’s a garage mechanic in an unbuttoned jumpsuit stabbed by a screwdriver in the abdomen. He’s a duelist in all white pierced by his opponent’s sword; a gymnast shot in the chest hanging suspended from gymnastic rings; a loincloth-clad fishmonger committing seppuku on the shop floor with fish guts scattered about; and a soldier in helmet and loincloth entwined in barbed wire.

Deadening in its repetition of death, the collection exhausts. With its generic and repetitive titles – “The Death of a Sailor,” “The Death of a Mechanic,” “The Death of Gymnast,” “Drowned Man,” “Hanged Man” and so forth – the “dead” body of Mishima is the only element that unites the variety of occupations and methods of dying. It embodies all too literally what the French literary critic Roland Barthes observed as “that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead.”

A careful orchestration

This collection of photos didn’t constitute Mishima’s first death in art.

As lead actor in the self-directed 1966 short film adaptation of his story “Yūkoku,” he performs a grueling seppuku. In Yasuzō Masumura’s 1960 feature film “Afraid to Die,” he plays a punk yakuza gangster who’s shot in the back, and he performs another seppuku as a samurai in Hideo Gosha’s 1969 film “Hitokiri.” In a 1967 photo shoot with bodybuilder-turned-photographer Tamotsu Yatō, he’s photographed dead in a snowy landscape, wearing nothing but a loincloth and clasping a katana.

But in this final collection, from conception to execution, Mishima was in total control. Unlike his earlier work as a photography model where he had given himself over to, as he put it, the “spell of the camera lens,” here he orchestrated everything. The vast majority of the images were shot on his command from early September through Nov. 17, 1970. He finalized the selections in a meeting on Nov. 20, 1970, just five days before his death.

Shinoyama would later complain that the project “wasn’t the slightest bit interesting” to him, and he bristled at Mishima’s micromanagement “down to the exact shade of red” for the fake blood.

The original plan was for this collection to be released in the immediate aftermath of Mishima’s suicide. Or at least this was Mishima’s plan. Instead, Shinoyama refused to publish the collection for decades and, in September 2019, angrily complained about being unknowingly made complicit with Mishima’s plan.

“Only Mishima knew. Even though it was a documentary headed for death, as the photographer, I was just an idiot.”

Our longing for preservation

Clearly, Mishima was obsessed with exploring death in art, in politics and in the bedroom. But his impulse – though extreme – represents something universal.

When facing death, whether it is our own or another’s, we confront the question of how – or if – the dead will be remembered. In our own case, we cannot help but imagine and perhaps even try to control the ways we will live on in the memories, objects and lives of our loved ones.

There is a longing for preservation, even immortality.

In Mishima’s case, this project of self-preservation was one he engaged with preemptively – before the fact. He recognized that although art may endure and offer one avenue for preservation, it was not without its own complications. In an October 1967 essay provocatively titled “How to live eternally?” Mishima mused at the difficulties faced by artists who inscribe themselves into their art – whether as an author of autobiographical fiction or as an actor in a film or play – in the interest of achieving what he called “a tricky, nasty immortality.”

Preservation is at the heart of this photography enterprise too. Death is not just represented but also suspended here, often quite literally, as in shots of Mishima propped in midair pierced by a dueling opponent’s sword or dangling from gymnast rings or ropes.

In a country branded as “the suicide nation” for its high contemporary suicide rates and historical associations with the act, Mishima remains, 50 years on, the most infamous example.

It is high time to put Mishima to rest. And this exhausting collection of images may just offer a means to do so.

The photo collection ends with a chapter called “The Death of a Samurai,” with Mishima in ritual whites and topknot committing seppuku in a series of six shots that culminate in his lightly blood-spattered figure prostrate in a contextless white vacuum.

But it is an earlier photo in the volume, the one that graces the cover, that offers some respite. It is simply a close-up shot of his face, unmarred and unbloodied. The background is shadowed while Mishima’s heavily powdered face turns upward toward the light. The title – “Death Mask” – offers the only context.

Relief in death and death in relief, at last.

Kirsten Cather, Associate Professor, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.