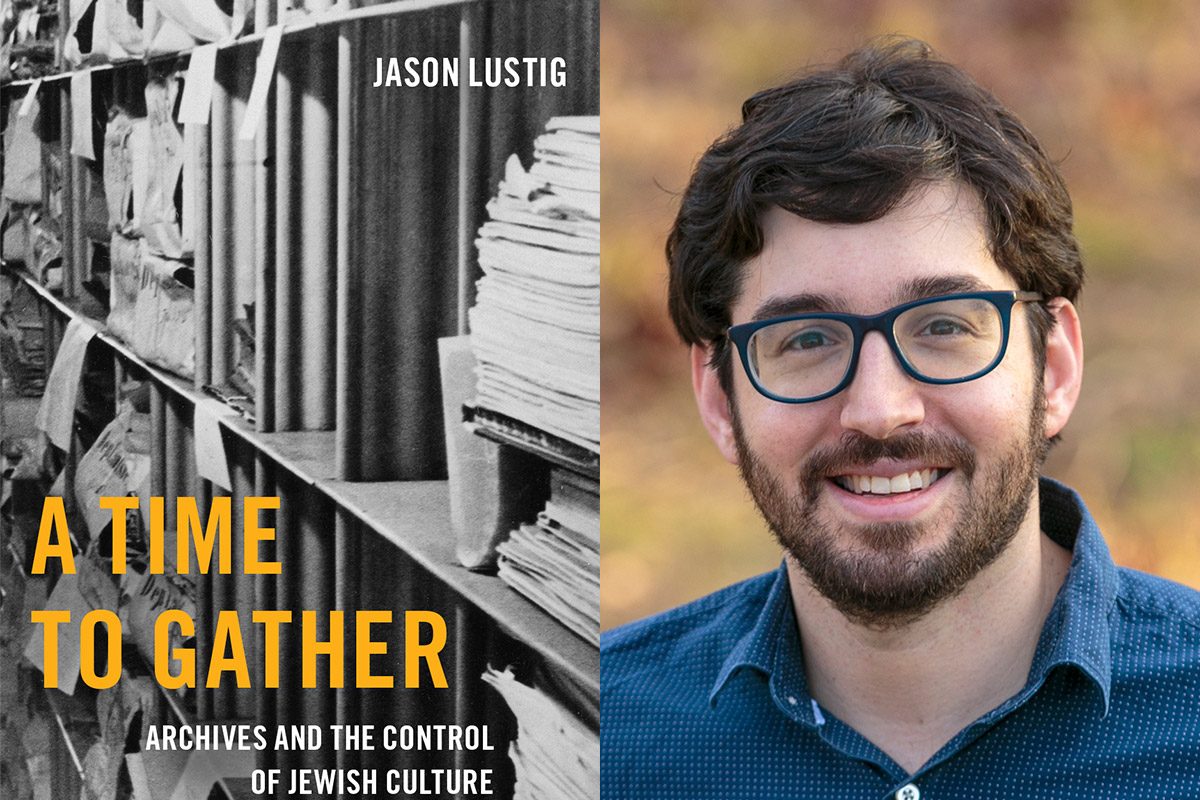

The following is an excerpt from A Time to Gather: Archives and the Control of Jewish Culture by Jason Lustig, lecturer in the Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies at The University of Texas at Austin. The book was published by Oxford University Press in December 2021.

A Time to Gather argues that historical records took on potent value in modern Jewish life because archives presented one way of transmitting Jewish history from one generation to another. They were also a way of making claims of access to an “authentic” Jewish culture. Both before the Holocaust and especially in its aftermath, Jewish leaders around the world felt a shared imperative to muster the forces and resources of Jewish life. It was a “time to gather,” a feverish era of collecting—and conflict—when archive-making was both a response to the ruptures of modernity and a mechanism for communities to express their cultural hegemony.

This brief excerpt explores the fate of the Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, the central archive of German Jewry based in Berlin from 1903 to 1943, and of its leader Jacob Jacobson. As the Gesamtarchiv was increasingly dominated by the Nazis, and eventually confiscated, the fate of the archive shows what was at stake in the control of Jewish culture.

The Nazi Party’s rise to power and the concomitant exclusion of Jews from public life led to a somewhat surprising strengthening of Jewish institutions, the Gesamtarchiv included. The archive serves as just one example of a trend that stretched from orchestras and operas to schools and synagogues, when German Jews simultaneously turned inward and toward the past: A marked increase in the number of historical articles in Jewish publications, which focused on figures like the twelfth-century philosopher Maimonides and Moses Mendelssohn, the godfather of the so-called German Jewish symbiosis, reflected history’s role as a mechanism for coping with the present, a reminder of good times gone by. In part, the Gesamtarchiv’s renaissance resulted from a June 1935 decree that restricted Jewish use of state archives. However, the archive’s higher profile was not limited to scholars, as the requirements of the Nazi racialist regime increased the Berlin archive’s prominence to unknown levels. As both Jews and non-Jews sought to document their racial status, public use of the archive grew geometrically. The archive received 1,812 inquiries in 1932, 3,107 in 1933, and 6,553 in 1934. By 1937 and 1938, between fifty and one hundred people came every day.

The rapidly changing environment of National Socialist Germany also transformed the Gesamtarchiv’s collecting activity. The Gesamtarchiv shifted its focus from the small eastern communities and now collected nearly exclusively from within the boundaries of Nazi Germany, showing an internal focus reflecting contemporary requirements to serve as a resource for both German Jews and the Nazis. Still, Jacob Jacobson’s emphasis on small communities remained. In a widely syndicated 1938 essay, Jacobson called on readers to “protect your archival material!” He emphasized the Gesamtarchiv’s role in collecting material from Jewish communities that in their day and age no longer existed, and he stressed that such “dwarf communities” were in danger of disappearing, populated by people without a proper understanding of their records’ value. Jacobson called on leaders to give their files to the Gesamtarchiv for genealogical research before their communities fully dissolved, and he exhorted “the community leader who . . . before he emigrated to America, transferred the archival material of his community to the Gesamtarchiv unbidden.”

The archive’s higher profile was not limited to scholars, as the requirements of the Nazi racialist regime increased the Berlin archive’s prominence to unknown levels.

Jason Lustig, A Time to Gather

In 1939, the archive was incorporated into the Reichssippenamt, the Nazi department of racial research, in part due to the Nazis’ increasing interest in the study of Jewish history. Years before the 1940 formation of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg, which infamously looted Jewish historical and cultural material, Nazi leaders expressed interested in Jewish records. In 1936, the Reichsinstitut für Geschichte des neuen Deutschlands, the Nazi “research” institute dedicated among other things to antisemitic propaganda, proposed that they confiscate Jewish archival materials. In preparation for Kristallnacht, Reinhard Heydrich specifically ordered Jewish archives be spared, and in its aftermath the Gestapo confiscated Jewish archives across Germany. In January 1939, Gestapo leaders discussed the fate of the seized archives and agreed that Jewish files should be brought together under Gestapo administration for political purposes. That March, the Gestapo occupied two of the Gesamtarchiv’s rooms and installed an officer to monitor the archive. Jacobson was provided with certain “advantages”—for example, he was not forced to wear the six-pointed star and could temporarily spare friends from deportation by employing them in the archive—but he became, in effect, a prisoner. Although his wife and son were permitted to emigrate to Britain in 1939, Jacobson’s own exit visa was denied, likely due to his “usefulness” for his archival knowledge. In the years that followed, Jacobson was forced to work as an “expert” for the Reichssippenamt, translating the Gesamtarchiv’s Hebrew documents.

Over time, the Reichssippenamt occupied more and more space in the Berlin Jewish community’s offices, eventually taking over the library, and Jacobson was forced to organize the Nazis’ archival collections on the Jews while his staff was gradually deported. In May 1943, the Geheimes Staatsarchiv (Privy State Archives) finally confiscated the whole archive, and Jacobson was deported to Theresienstadt. Still, he was able to salvage some material. Following his arrest, Jacobson was allowed to peruse the Gesamtarchiv and bring some files with him under the premise of continuing his “research” for the Reichssippenamt, which ensured Jacobson was provided with his own room, a typewriter, and even an assistant. Eugen Täubler later reflected that Jacobson’s “collaboration” presented him with the opportunity to save valuable historic material and to use the archives for the purpose of helping Jews in distress, noting that he was “an upright and couragious [sic] Jew in the Nazi-time: by rescuing large stocks of archives of Jewish communities that were not yet deposited into [sic] the Gesamtarchiv, and by utilizing these documents not only in scholastic interests but also for thousands of Jews who needed informations for the sake of their emigration.”

The bitter irony of German Jewry under National Socialism was that the policies of isolating the German Jews led to the achievement of certain goals long pursued by segments of the German Jewish community. The Reichsvertretung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich Representation of the Jews in Germany, formed in September 1933) and the Reichsvereinigung der Juden in Deutschland (Reich Union of the Jews in Germany, established in February 1939) respectively a representative group of the German Jews and a unified communal body, reflected German Jewish leaders’ hopes to form a unified body of all of the German Jews stretching back to the Gemeindebund’s long-standing vision of a Gesamtorganisation. Likewise, the growing utilization of the archive and the Nazi-controlled Jewish press’s constant publication of Jacob Jacobson’s call to protect archival material was not necessarily a new collaboration under duress but a continuation of the Gesamtarchiv’s well-established ties with the German state and further attempts to try to make archives a priority for the Jewish community. The activities of the Gesamtarchiv present only one example by which anti-Jewish policies led to the paradoxical fruition of enduring but long unattained Jewish aims enabled by working together with Nazi functionaries and state officials.

The Nazi takeover of communal institutions contributed to the day-to-day practical control of Jewish life in the aim of the destruction of the Jewish people and their culture.

Jason Lustig, A Time to Gather

The Nazis’ co-opting of the Gesamtarchiv and its eventual confiscation went hand in hand with the Germans’ broader program of looting and plunder, as the Nazis sought both to destroy Jewish life in Germany and throughout Europe and to expropriate it for their own nefarious purposes. During the war, the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg notoriously looted Jewish historical materials including libraries, archives, and other cultural treasures to Frankfurt am Main. As such, Jacobson’s fate was not dissimilar to that of Ernst Grumach, who was forced to work for the Nazis at the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, the Reich Main Security Office, or those scholars of the so-called paper brigades who were compelled to assist Alfred Rosenberg’s task force in sorting through the YIVO libraries in Vilnius and frequently smuggled material out of the ghetto. Crucially, however, the fate of the Gesamtarchiv under the Nazis was more than a matter of the looting of cultural property for the purposes of the “study” of the Jews. The archive proved a focal point of practical domination of Jewish life in Germany, more akin to the process of Nazi censorship of Jewish publications. The Nazi takeover of communal institutions contributed to the day-to-day practical control of Jewish life in the aim of the destruction of the Jewish people and their culture.

Altogether, the Gesamtarchiv increasingly became a pawn in the Nazis’ efforts to produce a propagandistic counter-history of the Jews and to place Jewish communal bodies under Nazi control. The dissolution of Jewish communities and their forced integration into the Reichsvertretung and the Reichsvereinigung, alongside the concentration of records at the Gesamtarchiv, presented corresponding parts of the Nazis’ program to destroy the institutional frameworks of Jewish life and make them easier to study and control. The fate of the Gesamtarchiv in the Nazi regime—first as a source of racial documentation, then as a resource for the study of the Jews by Germans, and increasingly under the direction of Nazi officials before its ultimate confiscation—sharpens the question of what it means to control Jewish culture and the practical place of archives in this dynamic. Turn-of-the-century leaders such as Martin Philippson had hoped the Gesamtarchiv would assist in organizing Jewish communal and institutional life, but here the role of archives turns potentially more sinister. As the Nazis took over the Gesamtarchiv, they marked how Jews had lost control of their history and their destiny. There was an element of political instrumentalization of Kristallnacht beyond the outward display of force against Jewish people and businesses: The events of November 1938 leading into the institutional changes forced upon the Jews in the summer of 1939 were part of a broad Nazi effort to dismantle Jewish life in Germany, and taking control of the Gesamtarchiv was one component of this directive to dominate and destroy Jewish life, communities, and cultures.

Jason Lustig is a lecturer and Israel Institute Teaching Fellow at the Schusterman Center for Jewish Studies. His research focuses on the development of Jewish archives in Germany, the United States, and Israel/Palestine in the course of the twentieth century, and the struggles over who can claim to “own” Jewish history, which is the topic of his forthcoming book. He is the host and creator of the Jewish History Matters podcast.