Youjeong Oh doesn’t have much time to watch television dramas anymore, but they keep following her to work.

“In fall 2021, everyone watched Squid Game on Netflix,” says Oh, an associate professor in UT Austin’s Department of Asian Studies. “Everybody watched, except me.” A dystopic South Korean drama in which characters compete to the death for a large cash prize, the show was a surprise runaway hit with global audiences, including UT undergrads.

“My students asked a lot about the show in class, and some even sent me links to summaries on YouTube,” Oh says. “I was interested in the kinds of minority characters that appeared in the show — North Korean defectors, migrant workers, those who didn’t have jobs, gangsters, all these people who are in the ‘negative’ side of the country. Many students have this kind of fantasy about Korea that it’s all fancy lifestyles, fashion, and beauty, but it’s always a theme in my work to open your eyes to the overall structure of the country. It’s not all necessarily good!”

Oh’s interest in the sociological underpinnings of Squid Game is no surprise. The overlap between Korean popular culture and the country’s material realities is one of her specialties.

As a scholar and trained geographer, she focuses on the convergence of pop culture, visual media, tourism, and local development, and she has long been interested in how and why people are drawn to visit certain locations presented in media and how those places shift and transform to accommodate visitors.

“Power is inscribed in projecting only particular aspects of a place among multiple competing values or in concealing a place’s material realities,” Oh says. “So, when a place is sold to tourists, outsiders get to briefly consume the surface qualities of a place, but local residents have to deal with the aftermath. I want people to think about that — about the distinctions between the representation of a place and its material realities.”

Oh wasn’t always a writer, or even a social scientist. Born on Jeju, South Korea’s largest island and a popular tourist destination, she went to college on the mainland and studied civil and urban engineering, then earned a master’s degree in urban planning. Her training was extremely technical, with an emphasis on hard numbers and quantitative methods. It was only after moving to the U.S. to complete a second master’s degree in urban planning that Oh was introduced to an entirely different approach to cities.

“That master’s program was really an awakening moment,” Oh says. “It included a lot of U.S. urban histories, and it was there that I encountered the humanistic perspective on urban issues. That really inspired me, and it put me on this path to re-training as a geographer and social scientist.”

Before “re-training” — completing her Ph.D. in geography at the University of California, Berkeley — Oh did have some time for television, and one show in particular would shape the rest of her career. While watching Yeon Gaesomun, a high-budget Korean period drama, she noticed MunKyung City and DanYang County listed high up in the closing credits of a particularly eventful episode. What usually sped by in a blur gave her a moment’s, and then a career’s, pause. Why were these areas credited? What was the relationship represented by that split-second place in a credit’s quick roll?

From those initial questions sprung the work that would become Pop City: Korean Popular Culture and the Selling of Place, published by Cornell University Press in late 2018. In the book, Oh investigates how Korean cities and regions use popular culture, particularly television dramas and K-pop, to promote themselves to an expanding audience of ardent fans. This can involve arrangements like the one she first noticed, in which rural areas of Korea sponsor television dramas in the hopes that fans will visit filming locations, or set-ups in which neighborhoods surrounding Seoul vie to host K-pop music videos. The specifics of each arrangement matter less than the impact of the whole. As municipalities spend more money and effort luring cultural producers, they spend less on supporting local communities and needs. In the pursuit of tourist dollars, urban and rural spaces are making themselves commodities to be sold, bought, and consumed, rather than places to live.

Oh argues that Korean cities are desperate to use popular culture to make and sell them-selves as “K-places” for a host of reasons, many rooted in recent history and local politics. Over the latter half of the 20th century, South Korea developed rapidly, and large urban building and development projects became a sign of governmental investment in the country’s well-being. That emphasis on development has continued into the present day, though now it’s often orchestrated by local and lower-level elected officials across the nation who see high-publicity development projects as key to gaining higher office. But development is expensive, and often far beyond the means of the country’s smaller municipalities. Partnerships with pop culture producers and accompanying tourism-marketing campaigns, on the other hand, are much easier on local coffers and have the potential to bring explosive publicity — exactly the kind of thing to make a career.

Oh points to the City of Incheon’s sponsorship of Goblin: The Lonely and Great God, released in 2016 and also known as Guardian, as an example of how a city’s sponsorship of a drama series can feed local tourism efforts. After the show was released, the city created the Goblin Tour, combining filming locations and local landmarks and restaurants. Incheon urged tourists to go on the tour and post their “tour stories” on social media, and even offered gifts to select tourists who did so.

But pop culture is always a bit of a gamble, both for producers and for sponsoring municipalities. Not every show is a hit; not every singer is a star. Even so, many areas — especially those without a wealth of local history or culture — are willing to roll the dice, hoping to score big. But when they do, who really wins?

That question runs through both Pop City and Oh’s larger body of work. In a paper released shortly after the publication of Pop City, Oh dug deep into the creation and use of an expansive mural project in Ihwa Village, one of Seoul’s oldest neighborhoods, in an attempt by central officials to drive revitalization. The murals were successful in drawing admirers, especially after appearing in popular television shows, but local reactions to the murals — and the crowds — were mixed at best.

By turning Ihwa into a play-ground for Instagrammers, Oh writes, the murals hid residents’ lived realities. As the murals and Ihwa Village became visible in more and more media — from television to Instagram — the meaning of the place became flattened, distorted. Rather than a neighborhood full of people living and working, Ihwa became seen as simply a pretty place for tourists to take photos and live out a brief fantasy. That bene-fitted some residents, particularly those who operated businesses that boomed with the increased traffic, but others resisted the attention and its downstream effects. Some even defaced murals and sprayed “We Want to Live Like Humans” and “How Come a Residential Area Turned into a Tourism Zone, Nonsense” on the sides of their houses.

That angry reaction was about more than the press of crowds, though. In the wake of the Ihwa tourism boom, the city government changed urban planning guidelines for Ihwa to prevent redevelopment and preserve the Instagrammable village. The change also affected the ability of residents to operate businesses in the area.

“As such zoning restrictions affect economic benefits, those whose houses belong to the ‘residential zone’ are protesting by removing murals and by graffitiing the walls,” Oh writes. “They also added the following messages: ‘Ensure Property Rights’, ‘Preservation for Whom?’ By erasing the public art that rarely engaged with the community, graffiti appears to manifest the real voices of some residents.”

While Pop City investigates the mechanics of a tourism machine powered by pop culture connections, Oh’s more recent work examines how social media can turn any visitor with a smart-phone into a tourism industry in miniature.

Once again, it was Oh’s students who led the way. They first introduced her to Instagram and then, a few years later, to TikTok. Though she doesn’t like to use the apps in her personal life — Oh finds the number and variety of images on Instagram overwhelming — she’s used them to incisive effect in academic articles that analyze how social media’s insatiable hunger for beautiful, repeatable images is reshaping areas and communities across South Korea.

Her findings aren’t very pretty: Like pop culture-fueled tourism, Instagram and the fantasies it fosters directly contribute to dramatic changes in tourism areas, and not always for the better.

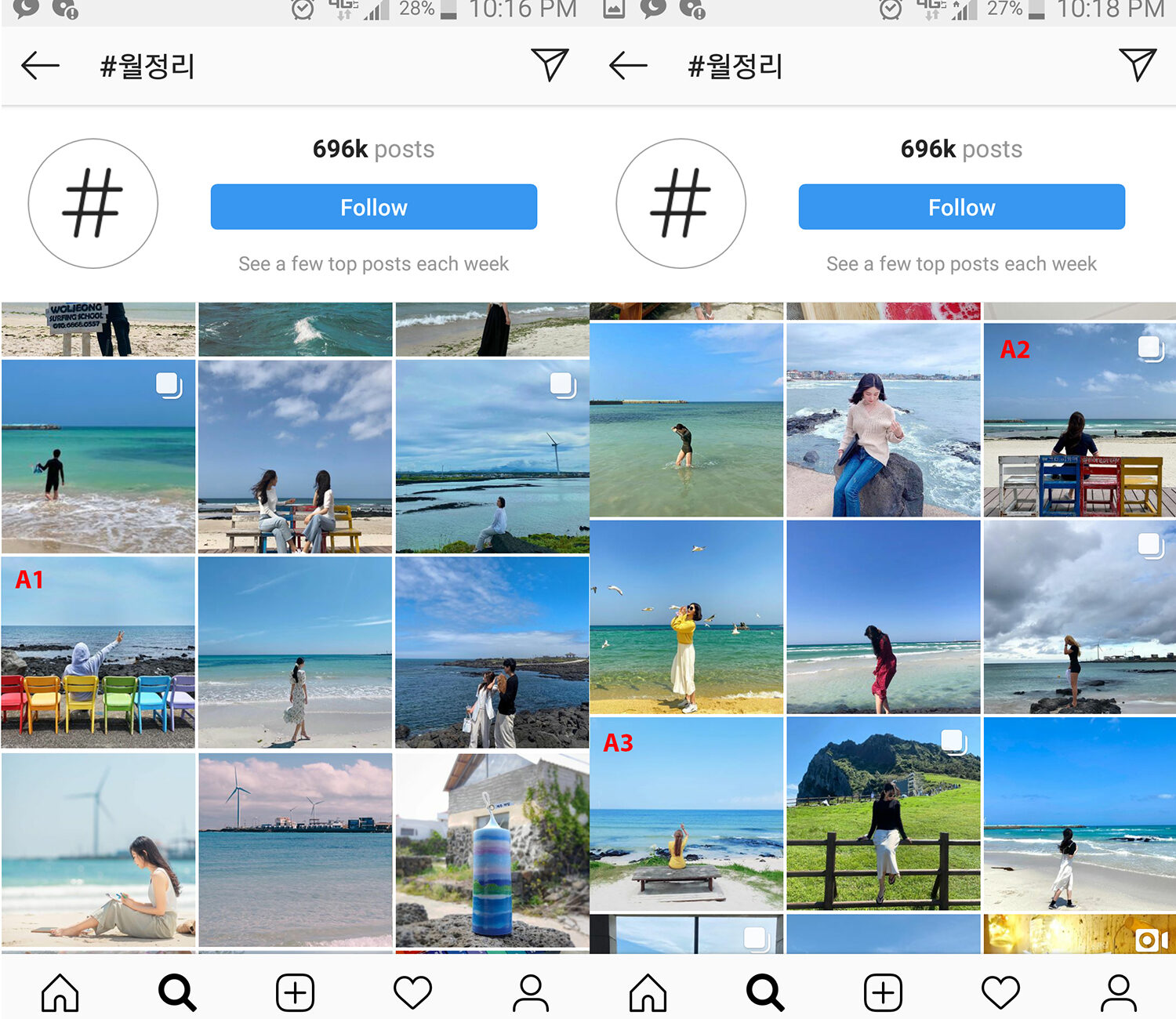

One of those articles struck especially close to home. It zeroed in on the downstream effects of viral photographs of a beach in Woljeong, a once-secluded fishing village on Jeju Island. A naturally gorgeous location, Woljeong was designated a UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site in the 2000s, but it was a series of photos taken a few years later and spread through then-popular blogs that made the village internet famous. As travel blogs began to give way to the even more popular Instagram platform, tourists began to pour into the area in search of similar images, bringing with them property value spikes, over-development, and gentrification. But just as important is what their photographs erase: The people who live in Woljeong, and the material realities of their lives, never appear in Instagram photos. Online, it’s as if they don’t exist, and if they don’t exist, they’re that much easier to displace.

“There’s a kind of hidden guidance on Instagram that the pictures are supposed to be perfect,” Oh says. “Jeju and the actual lives and landscapes on Jeju are very diverse, but the ways they are represented on Insta-gram are very homogenous. You see a photo of a sunset against this vast landscape, capturing someone’s back, and on the other side of the photo there’s a huge line of people trying to get the exact same photo. What does that mean, not only about Jeju but also about other tourist areas?”

“Tourism scholars talk about the ‘touristic gaze,’ which is really a colonizing gaze,” she continues. “By casting a gaze towards people and place, the tourists reflect upon themselves. They’re part of this urban cosmopolitan elite class, very high status, and by visiting these locations and looking at the indigenous people or the people in these tourist areas, they’re creating these power hierarchies. I’m trying to reveal how that gaze became more widespread and is actually driving material transformation in the age of social media.”

In Jeju, the effects of tourism development are visible almost everywhere. “When I say I’m from Jeju, many people say that the tourism on the island must benefit Jeju,” Oh says. “But, not really! That’s something I’m trying to reveal. Many operators are mainland capitalists, and they arrive on Jeju and kind of force the residents to sell their land and then start to establish some commercial facilities to try and sell the same place to the tourists. Local citizens rarely benefit. None of my family members, or extended family members, are beneficiaries of tourism development in Jeju. That’s the story.”

The development of the island continues apace, however, and with the relaxation of barriers to foreign investment, more change is on the way. Oh’s work is changing as well. She’s still interested in media and pop culture, she says, but her next project — a book tracing the history of development and dispossession in Jeju — marks a shift back towards her urban planning roots.

That book, which Oh hopes to finish in the next year, will follow the development of Jeju from the 1970s, when the central government of South Korea began to build tourism projects on the island, to the present. She argues that this history of development hasn’t benefited the island or the islanders but has instead allowed investors to extract profits from Jeju while displacing the locals from their ancestral lands, destroying the island’s collective and reciprocal economy, and leaving its environment permanently altered. Now, barriers to foreign investment in Jeju have been dropped, paving the way to even larger development projects — and even more displacement.

“Now, Jeju is open to internationalist city development that is mega-sized,” Oh says. “It’s making the island into the Hong Kong or Singapore of Korea.”

In turning her scholarship to focus squarely on Jeju, its complicated history and its near-daily alterations, Oh has larger aims than merely measuring development and its discontents. “As a Jeju-born intellectual, I am committed to initiating a dialogue of the previously overlooked chapters of Korean and East Asian history and the on-going controversies of overdevelopment,” she says. “In taking Jeju peoples’ demands for decolonization seriously, I am passionate to carry out my own praxis by documenting and communicating Jeju’s experiences.”