A Generational Look at Education, Money and Work

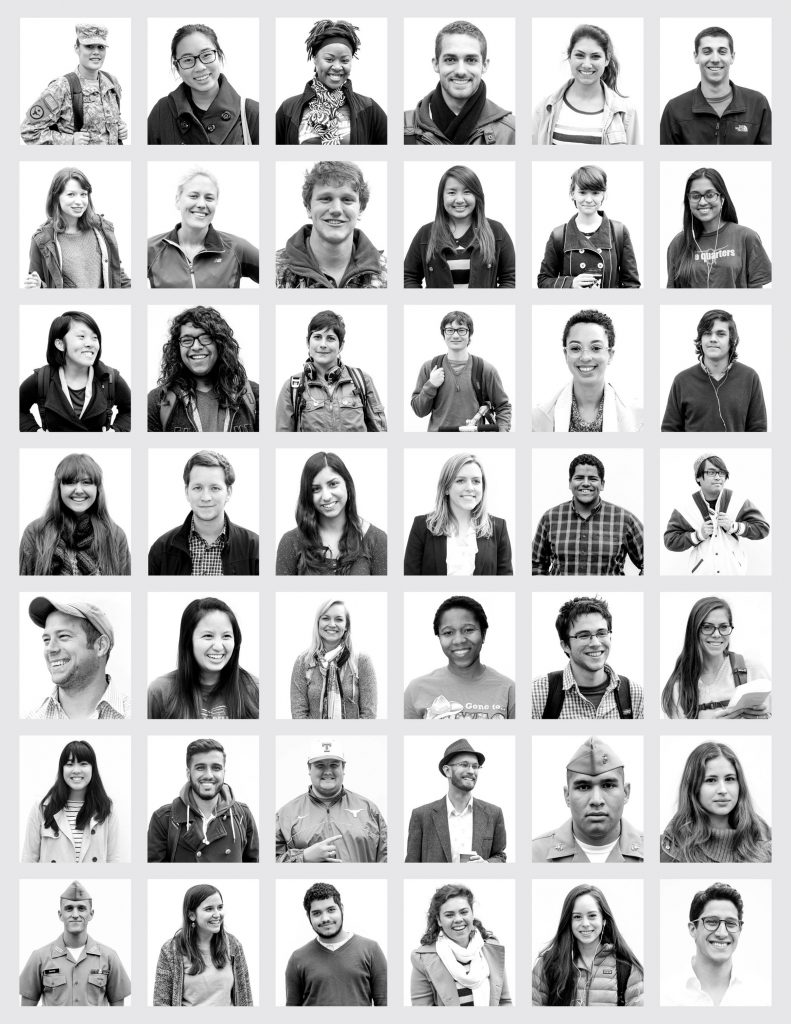

Empathetic. Impatient. Innovative. Unfocused. Rational. Naive. Excited.

These are the words millennials in the College of Liberal Arts use when they’re asked to describe themselves. However, it’s a question they’re not often asked.

Plenty of people, from journalists to researchers to employers, are looking to define who millennials are as a generation, but letting individuals within the group define it themselves seems to be a less popular idea.

The most standard definition of a millennial is someone who was born after 1980 and grew up during the new millennium. Their perspectives have been shaped in times of incredible economic upheaval, cultural change and increasing globalization. And of course, rapid technological advancement.

As anthropology and radio-television-film (RTF) junior Coleman Tharpe puts it, “Contrary to popular belief, we were not ‘born digital.’ Millennials were the first generation of digital migrants, and we colonized the digital world.”

Education is a forefront issue to millennials, many of whom have recently earned a degree, are attending college now or will soon be preparing to enter a university. Most of their major decisions revolve around how their education is going to affect the rest of their lives.

Earning a college degree is seen as more essential than ever before, and millennials are the most educated generation to date. In 2012, one-third of the nation’s 25-to-29 year olds had completed at least a bachelor’s degree, and another record-breaking 90 percent of the same group held high school diplomas, according to Pew Research Center.

“Growing up, I truly did not believe there was any other option outside of going to college,” says Asal Naderi, a Portuguese and public health junior. “College was the way I would become an influential member of society, and I simply had to go.”

Understanding College Debt

While higher education is fundamental to millennials, it’s also costing them much more financially than it did previous generations. Plan II and economics ’13 alumna Aneesa Needel borrowed more than $28,000 to pay for school.

“I have a lot of student loans,” Needel says. “They funded most of my education. Luckily, I found a job shortly after graduation and I’m slowly paying back these debts.”

One in five American households now owe student debt, according to a 2010 Pew Research study. That amount is twice what it was 20 years ago. National trends show that the average student loan balance outstanding in 2010 was $26,682, but 10 percent of student debtors owed more than $61,894.

In the 2012–2013 academic year, liberal arts students attending The University of Texas at Austin together borrowed more than $23 million, according to Miguel Wasielewski, program manager of research and assessment for student financial services.

The average cost of tuition, room and board and other expenses for a UT liberal arts student per year is $26,692. That’s a total cost of $106,768 for a degree earned in four years.

These numbers, however, are higher at peer universities. UT’s resident tuition ranks 10th among 12 peers, and the rate of its increase over three years (fall 2010-fall 2013) is just 4 percent, tied for the lowest percentage increase among 12 peers.

Tom Melecki, director of student financial services, says that the millennial generation is becoming more and more reliant on loans. There are two common types of loans that students borrow. The first are need-based loans, which are funded by the government and ensure that students don’t have to pay interest on them while they’re in school, or for the six months after leaving school. The other common type are unsubsidized government and private loans, where interest starts to accrue from the day the student takes out the debt and keeps accruing until the student pays off the loan.

“Many times, students are taking out unsubsidized loans because even after we give them all the need-based loans, they still need more money,” Melecki says. “That’s a direct result of a couple things—the rising cost of higher education is one of them. The other is that policy makers in Washington and down at the state Capitol have, in some cases, actually eliminated funding for grant and scholarship programs for financially needy students.

“I’m fortunate enough to live in an age where young people have the tools to be instigators of change.”

Nina Ho, French and advertising, sophomore

“In other cases, they’ve just held the funding steady, but with inflation, in real terms, that’s a reduction in funding. Therefore, students are more and more dependent upon loans,” he says.

Miles Hutson, an international relations and computer science sophomore, finances his education in multiple ways.

“I have about $10,000 in student loans, which will hold steady now thanks to being awarded an $11,000 per year Larry Temple Scholarship Endowment,” Hutson says. “My tuition is also largely paid for by a Texas Guaranteed Tuition Plan that my grandfather wisely bought before I was old enough to even understand what TGTP was.”

Melecki recommends that students carefully review the Office of Student Financial Services’ websites, including texasscholarships.org and bevonomics.org/ut4less, which can be much more informative than trying to sort through the options alone. Getting a clear picture of the expenses that come with college is crucial to help students and their families understand which financial aid options are right for them.

“A lot of the time, families won’t even need the entire loan amount that we’re offering them,” says Jamie-Lynne Brown, communications coordinator for student financial services. “I was just speaking to a student’s dad yesterday and once we were able to track down how much tuition and housing were going to cost, we figured out that he needed less than half of one of the loans he qualified for. That’s not how it is for everybody, but it’s good to at least give them the opportunity to see.”

When families are able to start preparation early it can make a world of difference in the amount of debt students accumulate.

“Fortunately, I don’t have any student loans,” says Patty Sanchez, a psychology senior. “My parents are excellent planners and prepared to pay for my college tuition from very early on. Since I am an only child, it’s a bit easier on them to pay for my education. This is probably the gift I am most grateful for from my parents.”

Taking Control of Your Budget

The millennial generation is highly motivated and committed to defining their futures on their own terms. Part of that motivation involves establishing themselves in the workforce early on. Having a part-time job while in school can also help students generate income, which leads to them borrowing less money to finance their education.

“It depends on the student, but generally working around 10 to 14 hours per week appears to be pretty manageable,” Melecki says. “As a matter of fact, national studies have shown that students who work around that number of hours actually earn higher GPAs and persist at higher rates than students who don’t work at all.”

Student Financial Services helps students find part-time and seasonal jobs through its website, hirealonghorn.org/students.

“They’re the ones who are going to think about ‘what’s next’ rather than ‘what’s now.”

Robert Vega, director of Liberal Arts Career Services

“I have two jobs and both are off-campus,” Naderi says. “I work about 20 hours per week. Working while going to school has taught me how to manage my time more effectively and how to be a smarter consumer.

“I try to pay back my student loans at the end of each semester through my own savings and job earnings. I plan to not be in debt by graduation,” she adds.

The entrepreneurial spirit is a signifier of both millennials and those who are passionate about the liberal arts. Nina Ho, a French and advertising sophomore, is one example of a UT liberal arts student who has gone out of the way to establish her brand.

“Working while going to school is hard but necessary,” says Ho, who works as a freelance graphic designer, social media manager and brand consultant. “It builds character along with time-management skills, and I’ve learned more technical skills being an entrepreneur than sitting in a classroom.”

Earning extra income is helpful, but learning to budget as a college student is perhaps the most important skill millennials can pick up. Unfortunately, budgeting isn’t something many students are exposed to prior to leaving the nest.

Because room and board is the biggest portion of students’ educational costs each semester, making sure housing is covered is crucial in creating a stable college budget.

“One of the benefits of living on campus is that when we process financial aid, we automatically apply it to tuition, then housing,” Brown says. “I’ve actually suggested to students living off campus to go to their apartment complex and pay off their rent for the rest of the semester with their additional financial aid, so that they also have a better idea of what they have to work with.”

Knowing how to manage the remainder of their income for the semester can be challenging to students. Precision is vital in keeping a balanced budget.

“People need to see what they can spend on a daily basis,” Wasielewski says. “We budget monthly, but we spend daily, so we have to know what we can spend per day, because any given day is an opportunity to completely break your budget.”

Students can use a variety of techniques to manage their budgets—from classic handwritten notepads to banking apps to spreadsheets.

Because millennials are so comfortable around technology, using newer budgeting tools can help those who weren’t raised on more traditional techniques.

“Students now have things like Mint.com, and the apps through Mint, that pull all of their spending in and tell them where exactly they’re spending their money,” Wasielewski says. “There are some technological tools out there that they can use—they just need to know to do it.”

Making Your Time Count

“The biggest way to cut back on the money you spend here is to graduate in four years,” Melecki says. “Students really need to ask themselves the question, ‘If I stay an extra year so I can pick up that certificate or double major, is that really that helpful to me?’”

There are a variety of reasons that lead students to stay in college past the four-year mark. Millennials want to make sure they’ve chosen the major (or majors) that will lead them into the right career.

“On the one hand, graduating in four years would mean I could be out in the job market much more quickly and with less debt to boot,” Hutson says. “On the other, taking an extra summer means I could graduate with more skills on my resume and a degree in both international relations and computer science.”

Like Hutson, many students need to weigh the benefits of staying for extra accolades, study abroad programs, changing majors or raising GPAs against the added cost of another year.

“During the 2012-2013 school year, liberal arts students borrowed an average $7,459 to pay for a fifth year and $8,249 to pay for a sixth year of school,” Wasielewski says. “In total, nearly $2.1 million in loans was used to fund these additional years.”

These trends demonstrate the steady rise in debt students acquire when prolonging their education. The right decision, as usual, depends on each individual.

“There can be other peak experiences in your life,” Melecki says, “They don’t all have to happen here on the 40 Acres.”

A Generation on a Mission

When graduation is behind them and their professional lives are ahead, millennials have garnered a reputation for being stubborn. Perhaps a more forgiving word is “determined.”

“I find that many of them are waiting for that perfect job,” says Robert Vega, director of Liberal Arts Career Services. “They wait a little bit longer than someone in Generation X would have waited, or the baby boomers for sure. They’re completely open to having these gap experiences where they’re going to go home and they’re going to wait tables—so they’re literally waiting—because that perfect job is just around the corner and they’re pretty confident that it will happen.”

So what do millennials value in a job? For many, especially those who were passionate about their educational experiences, it’s having access to a lifetime of learning.

“If I have a career that consists of me continuing to learn on a topic that fascinates me, I’ll be more than happy,” Sanchez says.

“If I have a career that consists of me continuing to learn on a topic that fascinates me, I’ll be more than happy.”

Patty Sanchez, psychology senior

A topic that can’t be left out of the ideal job equation is money. While millennials recognize its necessity, salary isn’t the most important thing to them when it comes to accepting a position. Among Americans ages 18 to 34, nearly nine in 10 say they either have or earn enough money now or expect they will in the future, according to a Pew Research Poll. That’s a telling statistic about the motivation millennials have in their job search, especially when their increased student debt is taken into account.

“While financial security is important, an interest in performing a job is what drives people to do their best work,” Naderi says.

This generation also has certain expectations when it comes to corporate culture.

“Millennials are much more mission-driven than previous generations,” Vega says. “They’re looking for that perfect job that’s not only going to support their lifestyle, but they’re also looking for a sense of community, meaning and mission in a variety of industries.

“It might be a corporation that has a great sense of sustainability, or a job in the public sector that embodies a sense of patriotism or it could be in some type of communications office that does PR or media for nonprofit causes,” he adds.

Ho agrees that the passion her generation holds in finding meaning within their careers is significant.

“I am so proud to be a part of a generation that’s more socially aware than its predecessors,” Ho says. “Technology has broken down the barriers of communication and I’m fortunate enough to live in an age where young people have the tools to be instigators of change.”

Millennials in the Workforce

Millennials are finding themselves instigators of many different types of change, including in the workplace.

“They’re coming into the workforce much more tech-savvy, with strengths in multitasking and creative thinking skill sets and capabilities,” Vega says. “I think millennials are great in team environments, at taking initiative and they really value feedback. They’re also very good at learning what works and trying to adapt to that.”

Although millennials have discovered how they work best, their skills and techniques can create a little more conflict in the office.

“A lot of hiring managers and managers in general do have some difficulty when it comes to managing millennials, especially if they’re managing teams that combine generations,” Vega says. “While they love feedback, millennials like to work in their own style. That might mean less structure and more independence, even when they’re working in teams. That can go against the grain for their co-workers and employers.”

The millennial generation is often accused of lacking stay power when it comes to jobs, but their job mobility may be more strategic than other generations think.

Among 18- to 34-year-olds, only 30 percent consider their current job a career, according to a Pew Research study. However, the same study indicates that millennials transition from job to career quickly. Of workers ages 18 to 24, only 11 percent consider their job a career, compared to 34 percent of 25-to-29-year-olds and a whopping 49 percent of Americans ages 30 to 34.

“For baby boomers, it was about getting into a company and staying with that one company your whole life,” Vega says. “Millennials are really about landing a job at one company and then immediately thinking about their next step. So where a Generation X member might change jobs every four and a half to five years, a millennial is probably changing every three or fewer years.”

Moving from company to company doesn’t look appealing on a resume because companies want to hire employees they can train and keep around for years, not ones who will jump ship quickly. On the other hand, millennials have found a way to advance faster in their careers than previous generations.

“In taking all these risks, taking these leaps between jobs, they’re actually moving up the ladder pretty quickly,” Vega says. “Millennials are finding themselves in lead management positions at ages much younger than previous generations have.”

Subject for a Generation

“A liberal arts degree is a generalist degree that makes you a specialist in an area that matters— people,” Ho says. “Technical job demands will always be in flux, but the demand for an understanding of human nature will never change.”

A degree in liberal arts seems to go hand-in-hand with the strengths of the millennial generation. It’s a formidable combination that won’t go unnoticed by employers.

“Liberal arts millennials are great problem solvers, they think critically, they’re creative and they’re open to learning new ideas and implementing those ideas in a structured environment,” Vega says. “Employers can identify those skills in a liberal arts student, despite a potential lack of experiences on a resume or a lack of hard business experience.

“Liberal arts students are the intellectuals, they’re the creative thinkers and they’re the ones who are going to think about ‘what’s next’ rather than ‘what’s now,’” he adds.

“Ultimately, I found it important to be in Liberal Arts Honors and the College of Liberal Arts because the world is too big and fascinating—and college is too expensive—for me to spend my entire college career narrowly focusing on a trade,” Hutson says. “I wanted an educational experience that would prepare me to view the world in many different ways.”

A degree in liberal arts works so well for millennials because it is beyond simply a career blueprint or a certification. It says something more about the person who holds it.

Perhaps Coleman Tharpe, an anthropology and RTF junior, sums it up best. “A degree in liberal arts is essentially a degree, in some aspect, of what it means to be human.”